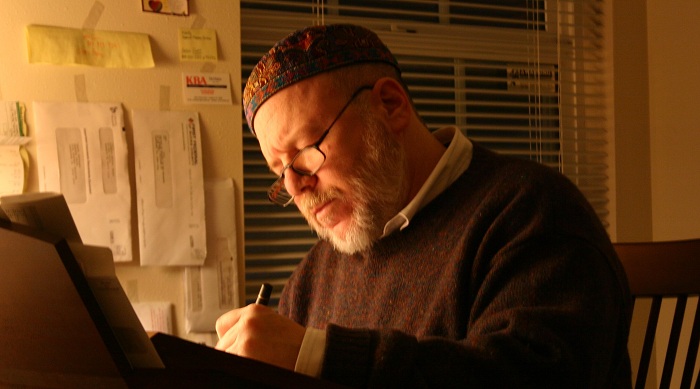

| No longer living in the suburbs, our

regular essayist Bruce Bentzman offers the first piece in his new series From the Night Factory 1. Atheist Grace I enjoy food. That is often a problem for me. I pay too much for food and I eat too much of food. I love food the most when sharing it with good story tellers and provocative thinkers who can express themselves. When it is at its best, I celebrate eating. As I have written elsewhere and repeatedly, eating is the opposite of dying. It must have been nearly twenty-eight years ago, soon after I met Ms Keogh, my more significant other, that we accompanied our dear, dear friend, Seki-san, for dinner at the Terrace [in the Sky]. Seki-san and I had eaten there plenty of times, but for Ms Keogh it was a first time experience and a bit disconcerting. One does not expect a fine dining experience upon entering the lobby of Butler Hall, a dormitory at Columbia University. A moment later to be whisked nonstop by an elevator to the elegant chambers on the roof, to be seated by an expanse of windows overlooking Harlem, it was very surprising for her, for me the first time, too. Sitting through a meal of many courses with aperitifs, wines, and then after-dinner drinks, was an experience to which Ms Keogh was unaccustomed. She was alarmed by the prices that exceeded practical meals that would feed a family for a week. She was also made uncomfortable by the austere gentlemen at the adjacent table who were annoyed by – well, let’s just say I grew more enthused as I ate and drank. Still, during that long meal, somewhere between the fading daylight and the appearance of the sparkle of lamps outlining George Washington Bridge across the Hudson, Ms Keogh was converted. Not just with the view. “I noticed the superb quality of the food, a level I hadn’t previously experienced,” she recently reminisced in a notebook. “I started paying attention to the smells, tastes, and textures of the wonderful meal.” Eventually, the food and the drink affected her. She no longer noticed the sour faces at the neighboring table. Instead she delighted in our company and what she called my joie de vivre. As we talked about the experience the other day, she said, “I wished you had been taking notes about what we ate.” I checked my journals and it had not been one of the meals I recorded. She recalled, “Everything was exquisite!” That evening, Dusan Bernic was the chef, a Croatian who, as a teenager, escaped Yugoslavia across the Austrian border. Sadly, not long after that wonderful evening, Mr Bernic succumbed to cancer at the too-young age of forty-three in 1985. Years later, when the three of us returned, accompanied by Seki-san’s brother-in-law, it was to be our last meal together. On the wall hung a painting of the late Dusan Bernic. It was a night of farewells. It was the last time we saw Seki-san, who returned with her brother-in-law to Japan and a few short years later she died. The restaurant is still there. Chef Bernic was survived by his wife, Nada, so the restaurant remains to this day in the family. Perhaps Ms Keogh and I will make it back some day. The best meals are always occasions to remember. I do not regret the fine restaurants we have patronized. I also recall fondly the many gatherings of friends, those feasts and banquets where we performed our own stagecraft and didn’t rely on waiters and chefs and sommeliers. Actually, with so many competent cooks among my friends, I never did. It fell to me to do the cleaning, and not just because I was the one who found the basil leaf in their soup. So it was, many, many years ago, my friends Ken and David had an apartment over the Pineville Post Office, a rickety building at a rural Bucks County crossroad, and they gave a dinner. The friends who once converged there are now dispersed; Ken is as far away as California and David has gone to Alaska. It must be said that only a few of us are as close to each other as we were then, for we have dispersed in our philosophies as well. That does not diminish the joy of the memory. And because I was an Atheist, am one still, I was asked to compose a short prayer to represent the honorable opposition as grace was to be performed by Mary, who was attending a Theological Seminary in Princeton at the time. As much as I enjoy food, I never take for granted the sacrifice that brings every delight to the table. So I wrote, in the form of a poem: atheist grace let us thank our judicious cooks this is not manna for it comes unwillingly to our table torn from vines uprooted slaughtered god’s grace provides little seasoning understand the cannibal christian magnanimous christ gave flesh and blood as sustenance died violently as food for thought and cows know fear when their skulls are cracked perhaps we are a special breed of cattle to sacrifice ourselves to gods so they can eat souls without guilt but this poet will be a bitter taste in their gluttonous mouths blessed are we that eat and are not yet eaten let us bow our heads and feel guilt which entities now lifeless never felt nor gods admit to in their havens and more vanity still let us apologize whereas this turkey was never vindicated to the worm and the worm never exonerates itself to us be satisfied yourselves as i will that to flesh or plant or even minerals i can apologize because i am a man Mr

Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about the events and

concerns of his life. If you've any comments or suggestions, he

would be pleased to hear from you. |