|

From the Night Factory

14. The Mütter Museum

Philadelphia has an abundance of museums. Until recently, the Mütter Museum was among those that I had never visited. Its home is in the the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, a medical organization founded in 1787 by medical men wishing to advance the science of medicine and reduce human misery. This noble purpose resulted in a museum collection of disturbing curios.

Since it is a medical museum from the 19th century, its two floors and side galleries are stuffed with oddities and monsters. In glass display cases and cabinets are curiosities collected for observation and study, including human remains of the most disfiguring and tormenting diseases. Presented to the public are skeletons and preserved body parts from victims who suffered deforming illnesses, and freakish foetuses trapped in bottles; a few items are wax recreations, but many more are the bits and pieces of actual cadavers. Also exhibited are the tools of the 19th century medical trade, which look more appropriate for the Inquisition.

The ancient Romans referred to a victim of genetic abnormality as lusus naturae, a ‘jest of nature’. For many of these through the ages, survival was unlikely, and they could be offered no help beyond the consolation of religion. Not until the Age of Enlightenment and the intervention of human reason did real hope begin.

It was at the Mütter Museum that I first learned of the sad condition of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, where the muscles and tendons slowly turn to bone, a particularly cruel disease. At age ten Harry Raymond Eastlack, Jr. broke a bone in his leg, starting the process. His body slowly ossified until, just before his death thirty years later, all he could move was his lips. It was his own request that his skeleton be donated to the Mütter Museum to foster research. That was in 1973. There is still no cure and it is fortunate that the disease is extremely rare.

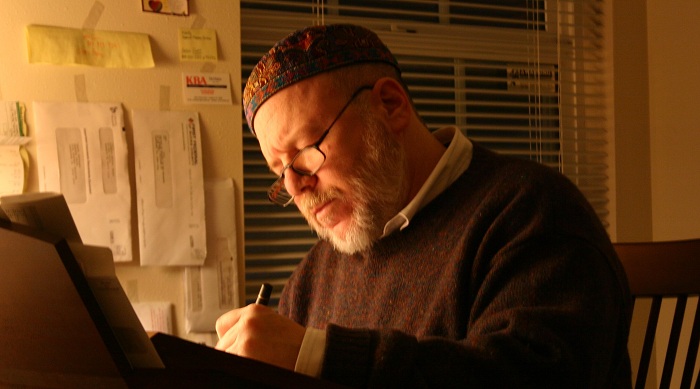

I sat down before a glass cabinet in which six skeletons were hanging and took out my sketchbook. I am not very good at drawing and have never had a formal lesson. At age sixty-one, this was the first time I took the time to make a study of the human skeleton. What I was discovering late in life was basic knowledge for any serious artist, what every art student must learn at the beginning of his or her career. It was, for me, a profound surprise that the proportions I thought I knew were wrong. It was no wonder my figure drawings never appeared correct. I had been clueless that the pelvis divided the body into equal halves and that the legs had been so long. I became particularly mesmerized by the bones of the feet.

What are feet but obviously deviated hands? I look at those five dwarfed fingers we call toes and realize they no longer serve any purpose except to provide a foothold for fungal infections.

At the museum, I was looking at the bones that fill our fleshy appendages; the foot has too many articulated parts that are fragile and unnecessary to their purpose. It could be better engineered for standing, walking, and running, if evolution didn’t have to restrict itself to adapting what came before. It is plainly the vestige of our former arboreal existence and one could wish for an intelligent designer to intervene, throwing out the old blueprints and starting from scratch with one efficient toe, like a horse or satyr. It would have certainly been easier to draw.

A great sadness touched me, reflecting on what a living nightmare life must have been for those who were inflicted with these extraordinary diseases and genetic abnormalities. For all the evil humans do, it made me proud to think how physicians work to intervene, to prevent tragedies, to reduce suffering and elevate comfort. The museum reminds us that we should continue to want to advance the science of medicine and reduce human misery.

I came away from this museum feeling lucky, amazed at having been spared so many horrors, grateful to have been born in 1951 and not 1851, when I probably would not have survived childhood because of an intussusception - or maybe it was a volvulus.

This is a ghoulish museum, a ghastly phantasmagoria, yet that is why the Mütter Museum attracts visitors. It is entertainment for 12-year-old boys. Also, for teenagers feeling alienated, ostracized, or rebelling against the commonplace; here they can find symbols of nonconformity made manifest, the strange appearances becoming their iconography.

Mr Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about the events and concerns of his life. If you've any comments or suggestions, he would be pleased to hear from you.

Recently published: Mr Bentzman's new collection

of essays from Snakeskin,

Selected

Suburban Soliloquies.

Also available

The

Short Stories of B.H. Bentzman

and his collecion of poems, Atheist

Grace