|

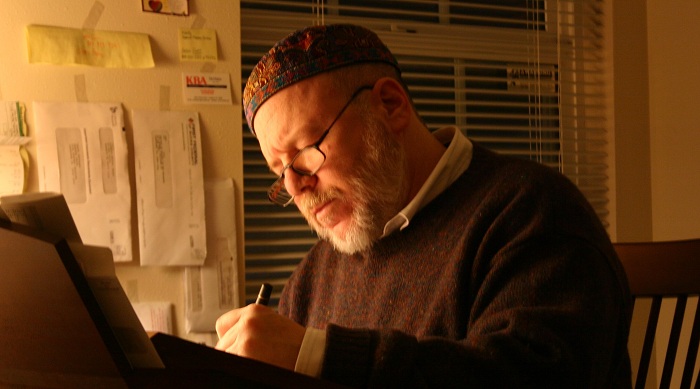

From the Night Factory

23. Old

When did I become old? At an early age, I divided life into three equal parts. I had decided youth was the first thirty years. Middle age was from thirty to sixty. Old age began at sixty. If you passed ninety, you had reached extreme old age. No one agrees with me. Dictionaries don’t agree with me. In my culture, people often resent being old. Youth lasts the longest, but only because it is arbitrary and people want youth to last the longest. When youth has obviously escaped them, and many acknowledge this too late, they cling to middle age. Anything is better than old age.

I depart from that vanity. My numbers are no less arbitrary, but I prefer them because they strike me as fair and balanced, and my numbers dispensed with the ever changing criteria bent to suit how some folks wish to be viewed. There is too much irony when someone insists on being regarded as young despite a conspicuous appearance otherwise.

I turned sixty in 2011. It remains my favorite year ever. Ms Keogh, my more significant other, and I had escaped the house and the responsibilities of home ownership. We moved into the first apartment I ever liked. That year included two glorious drives across the continent, the second one with our grandson, Mr Beckles. We were enjoying the income that came from my pension and severance pay, every two weeks a paycheck without having to go into work. Being sixty didn’t feel any different than being fifty-nine. In fact, it felt better. Having been laid off from my job in 2010, certain tics vanished, I found myself losing weight, and I stopped biting my nails. 2012 was a different story.

Warm days of spring had returned. Ms Keogh suggested we should play tennis. It was a beautiful morning. A bit damp with dew and mist hung about, but the sun was bright. Ms Keogh had just climbed out of bed not long before, but woke with the stirring desire to play tennis. I, who had been up all night, yielded to her exhilaration.

How long had it been, six months or a year and six months? I felt uncertain about my ability, fearing that my muscles would have forgotten the game and be uncoordinated from the lack of practice. I was never a good player, but I regarded myself a better player than Ms Keogh. She had not played in an equally long time and I felt confident I could beat her.

We faced each other across the court and I was feeling good. There was a little miracle. I had watched a women’s tennis match not long before on a television in a diner where we ate brunch with my mother. I noticed the way one of the players had served. Whenever I served the ball, the edge of my racket would tap my back, sometimes unpleasantly hard when my enthusiasm was engaged. I knew this was wrong, but I never knew how to avoid it and still have a good full swing. The memory of what I had seen on television came back to me; it was a particular looping sweep. The player was not hitting her back. That morning I endeavored to copy that serve and to my utter disbelief, it worked, first time, ace shot. There it was, I was sixty-one years old and I had discovered I could serve more comfortably, more powerfully, and more accurately than before. This was a boon that brought the promise, with practice, of a superior level of performance.

O, I was glad that morning with an optimistic perspective of what my life could be and I threw myself wholeheartedly into the game.

The ball was in play. Ms Keogh didn’t connect quite right and the ball came off her rim. A moment passed when I should have already been moving, but I wavered. Would such a weak ball make it back across the net? If I did, did I really want to bother going after it? It barely passed over the net, but then I saw there was a chance I could yet intercept it. I was there for the exercise, had been chasing every ball Ms Keogh launched at me, even if it was going out-of-bounds, and this one was doable. I dashed.

I was almost there, mid-stride, when there was a loud POP!, a sharp pain in my calf, and the leg wanted to collapse under my weight. It was the “pop” that disturbed me the most. I had never experienced a “pop” before.

“Something is terribly wrong,” I announced to Ms Keogh. I explained to Ms Keogh what I had heard and described the terrible pain I was feeling. I thought it might be a bad idea to continue playing, unless she, a retired Physician’s Assistance, thought otherwise. I told her, if she advised it, I would try to continue playing, even though my leg was advising me that it would fold if I attempted it. It was the “pop” that concerned Ms Keogh, too. She suspected that I had torn my Achilles tendon.

She helped me to hobble back to the apartment. She demanded me into bed and built a platform to raise my leg. She conferred with Google on her diagnosis and determined she had it right, that I had torn my Achilles tendon where it begins in the calf. It was only a matter of determining how serious the tear was.

It was not too serious. I walked with a cane for a few days. It was sore for a week or two. Soon enough the pain went away completely. But it left a scar in my psyche.

In my mind, I reviewed the incident over and over again. I was not overly exerting myself. The effort to reach the ball, it was well within my expectations based on experience of what I had always been able to do. What had happened? Why did this reliable muscle give out so suddenly, not even a prior indication that it was ailing and would not be up to the job? I felt betrayed. The cord of Achilles quit on me without warning.

That “pop” a year ago was the threshold. That is when I became “old”.

Mr Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about the events and concerns of his life. If you've any comments or suggestions, he would be pleased to hear from you.

Selected Suburban Soliloquies, the best of Mr Bentzman's earlier series of Snakeskin essays, is available as a book or as an ebook, from Amazon and elsewhere.