|

From the Night Factory

45. Tsundoku

In recent days, I have spent a lot of time contemplating the spines of books on my shelves. Usually the dilemma is what should I read next, but these days it has been to think how I might best dispose of books, or store them, or ship them across the Atlantic? Which ones do I keep? It is an impossible task that begins with reminding myself that I am mortal and a slow reader.

On 19th August, Ms Keogh, my more significant other, and I set sail on the Queen Mary 2 for Southampton, England. It is a one-way fare. Ms Keogh, a British subject, is returning to her homeland to live after a long fifty years away. She is taking me with her. We disembark on the 27th of August, two elderly bohemians beginning life again. Our first quest will be to find a place to live in Wales.

We leave almost everything behind, arriving with as many clothes as we can carry and some pots and pans. As for my books, they are too heavy and too many. Ms Keogh wanted me to sell the books to help finance our search for a new home, taking only as many books as we could fit into our luggage. “Sell them,” she said. “Shipping would be expensive and where would we ship them to?”

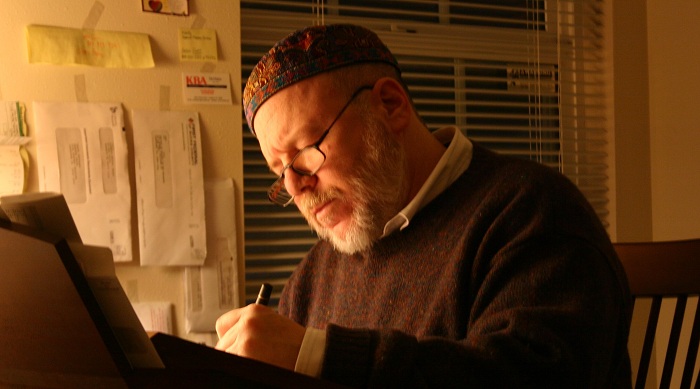

I have been collecting fine press books my entire life. Less frequently in recent years. Before I could afford them for myself, I would select a book and my father purchased it for me. One does not need a fine press edition to enjoy the utility of a book. I am not averse to paperbacks or books borrowed from the library and, in fact, I have two Kindle e-readers. All books serve as food for thought, yet the fine press book is a gourmet meal.

It begins as a coffer that draws the eyes, an invitation to search within for jewels. It occupies the hands, a tactile craftwork with comfortable weight to suggest promising content. It is satisfying to manipulate, turning leaves like opening doors or peeling away layers to continue deeper. Having the book illustrated, which my father and I preferred, is to have a museum in a box, a treasure chest of thoughts and aesthetics that begs not to be taken for granted. You travel through a book measuring the journey’s distance in units of pages and grow from the experience. Typography is the road. In a fine press book, the roadways should befit the landscape and be smooth to traverse.

Ms Keogh has begun sorting through the books, starting with the shelves in the living room. She emptied one bookcase of its books, perusing them and returning those to the shelf that she does not want to part with, 13 in all. The rest were brought into my study and now rise from the floor in two piles adding up to 31 books. There are three more bookcases in the living room, three here in my study, and one more in the bedroom. I have convinced her to suspend the process until April. “Why?” she asked. I needed to digest what was happening. I asked for the chance to compose my thoughts, telling her I would put them into this essay.

In 1929, George Macy, a bibliophile, launched the Limited Editions Club. He would issue twelve books a year produced at the very best presses on the finest papers. The books would be mostly classics, shaped by leading graphic designers and renowned illustrators. There would be only 1500 copies, a restriction that maintained their quality while allowing them to be reasonably affordable. He launched his Club the same year as the Wall Street Crash, yet it wasn’t long before all 1500 subscriptions were filled and those who missed out went on a waiting list. His beautiful books continue to show up at bookstores, auctions, estate sales and are typically undervalued. A few have appreciated shockingly.

My father joined the LEC in the 1950s. He was assigned number 1157. I have decided I would sell The Complete Poems of Robert Frost which I had inherited from my father.

Designed by Bruce Rogers, the two volume set is illustrated with wood engravings by Thomas W. Nason. There on the colophon with my father’s number, 1157, are the signatures of Frost, Rogers, and Nason. It has increased in value to where I am uneasy owning it, let alone risking the battering it might receive with transatlantic shipping. Besides, I have read it, several times.

George Macy died of cancer in 1956. Bruce Rogers died the year after. My father allowed his membership to lapse. At Macy’s death, first his wife Helen, then later his son Jonathan, continued the LEC until it was sold in 1970 to Boise-Cascade, a paper manufacturer. They then sold it to the magazine publishers Ziff-Davis. Next it became the property of Cardavon Press, headed by Gordon Carroll, a former editor at Reader's Digest and whose previous stint was as Director of the Famous Writer's School, which was determined to be a notorious scam. It was at this time that I became a member, assigned number 733.

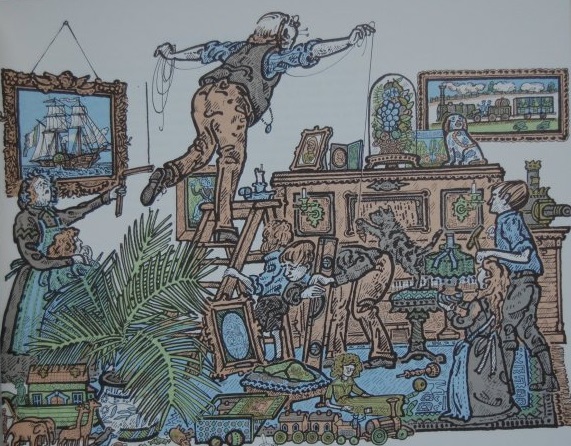

It was not a good time for the LEC. The books were pretty, but they lacked refinement and sophistication, were less dramatic, less diverse in source of production and style. Their designs needed more input from the artist. One of the books from this period was the hilarious Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog) by Jerome K. Jerome.

One of the illustrations for the Limited Editions Club Three Men in a Boat, by John Griffiths.

The edition was flawed. Two of the illustrations were transposed causing them to be out of sequence and not coinciding with the text. I wrote a letter of complaint. They informed me there was nothing they could do, except they offered to swap the book for another from a previous series. I wrote a second letter that I couldn’t part with the book despite its flaw. It was the funniest book I ever read and I was happy with how it was presented. My letter was long, sharing with the folks at the LEC my heartfelt appreciation for the components of a fine press book. My letter unexpectedly softened their original stance. They asked me to send the book and they would repair the mistake at their own expense. I now possess the only copy with the illustrations in their correct order.

The Cardavon Press sold the LEC to retired Wall Street broker Sidney Shiff in 1978 and the books again became magnificent. One day, during a stroll in Manhattan, I found myself at a golden archway, the façade to the Fred F. French Building on Fifth Avenue. I knew the address and that it held the offices of the LEC. Uninvited, compelled by curiosity, I went in and visited the LEC. So it was that I met Mr Sidney Shiff. I don’t think members often showed up unannounced, but he was very gracious. Despite being a whirlwind of activity, he quickly engaged me in seeing books and artwork in development.

I did not stay a member long after Shiff took the helm, but it was not for want of adoration of the books he produced. Under his leadership, the volumes became art books, objets d’art. The cost of membership outpaced my income. Yearly subscriptions rose from hundreds of dollars to thousands of dollars. The number of books in a yearly series diminished from twelve to four or fewer.

In March of 2010, Sidney Shiff died and ownership of the LEC went to his wife, Jeanne Shiff. It is not clear to me if the LEC still exists or, if it does, is still producing books.

There was a time when Philadelphia was dotted with independent bookstores chock-full of books that once belonged to others. Collectors spend their lives selectively acquiring books of a kind, a never-ending obsession which, more often than not, are then dispersed when they died. Well-made books returned to the market place to be redistributed among new collectors. They come in waves. Most of the LEC books I own were bought this way and not through my subscription.

Forty years ago, I paid a visit to Sessler’s on Walnut Street, one of Philadelphia’s legendary bookstores. Charles Sessler, a Jewish immigrant, arrived from Vienna in 1880 at the age of 27 and with $40 in his pocket. He opened his first bookstore in Philadelphia in 1906 and became a valued agent of procurement for the city’s famous collectors. He died in Philadelphia in 1935 leaving the store to his son Leonard. Leonard died in 1951, the year I was born. On this particular day in the 1970s, I was browsing the bookstore. It had changed in the time I knew it, had lost its former elegance and had become disheveled. I found my way to the back of the store and a wrought iron gate behind which were the books that interested me. I engaged in conversation the new proprietor, Mabel Zahn, who sat at a large desk behind the locked grate. From my view through the bars, I admired the beautiful books that surrounded her and she invited me in.

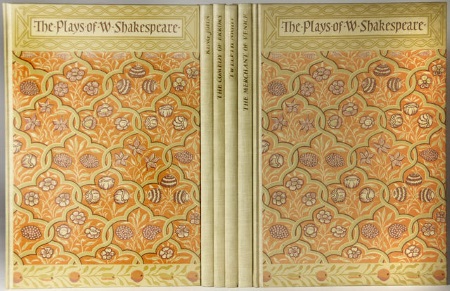

Mabel Zahn had begun working for Charles Sessler when she was 15. Now she was in her 80s and an authority on the handwriting of the Founding Fathers of the United States. In that room, I discovered the Limited Editions Club’s Shakespeare, a row of 37 tall, thin volumes, each illustrated by a different artist and the whole designed by Bruce Rogers to resemble the original folio.

The set included an additional two volumes of Shakespeare’s poems and a volume titled Shakespeare: A Review and a Preview. I had to have it. I couldn’t afford it.

Mabel Zahn was kind. She felt my enthusiasm and sold me the set on a layaway plan. Bringing further payment on each visit after that was nerve-racking. Her mind was dull with age. At every visit, I had to reintroduce myself, because she couldn’t remember me. I was afraid she would lose the records of my payments, she probably being the only one who knew where the paperwork was kept on that cluttered desk. Yet each visit renewed our friendship after a short effort and she would share with me treasures hidden in her desk drawers. One in particular I remember was an ornate scroll of calligraphy, the Book of Esther.

The last payment delivered, I came away with my books. Soon thereafter, Mabel Zahn died. Sessler’s Bookshop had lost its soul and a few years later, it, too, died. Meanwhile, I spent that next glorious summer reading the entire collection. Having read them all, I suppose I should now sell the set.

Not even half the books I own are LEC, nor even fine press volumes. Still, I did see my collection of books as an investment in my retirement, just not a financial investment. They were a cerebral investment. They were an emotional investment. They were meant to enrich my days when I no longer had to consume the hours in earning an income to support my family.

“You’ve been retired over four years, how many have you read so far?” Ms Keogh’s argument was sound. “At least reduce their number. There will be books in Britain, too. They have bookstores and libraries.” I looked at the dozens of Folio Society books I own; would shipping them just be returning coals to Newcastle? Again she reminded me, “You don’t have to sell them all.” Triage!

I ponder my dilemma surrounded by rows and piles of my books. What is the best way to send books to Britain? What is the safest way? How many can I afford to ship and where will I ship them to? We don’t have a place to live yet. The plan is to find a place once we are there. I will need a friend, someone with room for my books; someone who might enjoy rummaging through them and finding a few to read until I can fetch them.

The books were never mine. I have merely been their steward. They were always on loan, destined to continue to other readers until they fell apart. But I never intended to part with them until I had read them! That’s how it was supposed to be.

The Japanese have a word for it; “tsundoku”, which is the buying of books without ever reading them, allowing them to pile up around you.

Mr Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about the events and concerns of his life. If you've any comments or suggestions, he would be pleased to hear from you.

Selected Suburban Soliloquies, the best of Mr Bentzman's earlier series of Snakeskin essays, is available as a book or as an ebook, from Amazon and elsewhere.