|

88. Moving Art

Why do we preserve art? Even on a small and personal scale, Ms Keogh, my cherished companion, and I gave special attention to our art collection when we moved, though to little else. We regularly visited museums and galleries, and would measure the worth of a work of art based on whether we could live with it. Would we have a certain piece in our home where we would see it day in and day out for years?

In the last month of 2010, my having completed a 31-year career at AT&T, Ms Keogh and I moved from our three-bedroom house in suburbia to a two-bedroom apartment. Meanwhile, our daughter moved into the house we had vacated. It had been my parents’ house before it was mine. I had been calling it home since 1961.

In addition to such stuff as Ms Keogh and I had accumulated, it held a lifetime of debris from my parents and the childhood possessions of our son and daughter. There was no room in our new apartment to take everything that belonged to us and, since our daughter was willing to store items for us, we left things behind. We also gave her the furniture and bought everything anew. But we took as much of the artwork as we could squeeze into our apartment to either hang or store.

In August of 2015, I fulfilled a promise and took Ms Keogh home to live out the rest of our lives in the United Kingdom, where she was born and lived her childhood, and where most of her family resides. We gave our daughter all the new furniture from our apartment. All the artwork came out of their frames so we could carry as much as possible in the luggage we brought aboard the Queen Mary 2. A greater quantity we mailed in tubes to Ms Keogh’s youngest brother in England. The rest, the least valued, went back to the house for indefinite storage.

Our first apartment in Cardiff was a tale of woe. Nevertheless, we tried to make a home of it. Ms Keogh found a framer she trusted and began unpacking artwork to be remounted and hung on new walls. She chose the first pieces because it was understood she wasn’t expected to live many more years, suffering all her adult life from chronic renal failure and it was taking its toll. We couldn’t tolerate that fetid apartment and moved before the year-long lease was up. We found a better apartment in the heart of Cardiff, rooms we so loved we intended to live the rest of our lives in them. Ms Keogh died nine months ago, but it remains my hope to continue to live here and be haunted by her.

It was always best where our tastes overlapped, but we often favored different pieces. We each had the power of veto. We had begun by favoring the art she liked most. Now it was time to hang the art I liked most. Ms Keogh’s original framer had vanished, but before Ms Keogh died, she had found another framer she trusted even more. It would be the same one I used.

Having decided to have three pieces done at a time, the first three have been completed and are hanging on the walls. They serve as additional windows that allow me to peer into memories others will not see.

The largest piece, 29” x 25” in its frame, is the one reproduced at the head of this essay, an ink drawing made by Antonio Gattorno in 1942. It is the head of a skinny man with a suspicious expression and a bizarre hat or helmet. There is a wicked appearance in his long and bony fingers with their pointed nails. The drawing was a gift to me when I took my mother to Providence, Rhode Island to visit with the artist’s widow. I remember the three of us relaxing on Isabel Gattorno’s bedroom floor with glasses of wine as she brought out her husband’s drawings. Isabel took note of how enamored I was with this one drawing and she gave it to me. I was surprised and embarrassed, telling her I didn’t merit it and that she could probably sell it. She insisted. My mother, taking note of Isabel’s generosity, asked for three additional drawings, which further surprised and embarrassed me. Isabel relinquished them as well. My mother never framed them, never hung them in her apartment. I have them still, stored, and don’t know what to do with them.

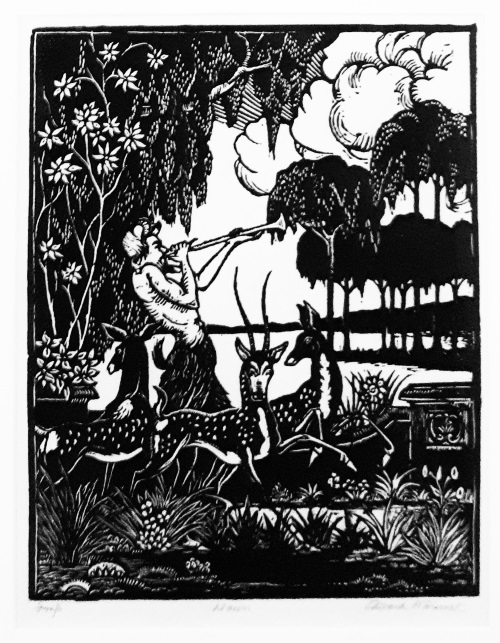

The second piece is a block print by Edward Warwick (1881-1973) titled “Dawn”. I cannot tell if it is a woodblock print or a linoleum print. He is known to have used a hard linoleum manufactured in Philadelphia specifically for the decks of aircraft carriers. The image shows a satyr, perhaps Pan himself, blowing a horn in a wooded paradise by a lake and surrounded by gazelle-like creatures that I suspect you would not find in Greece.

I had belonged to the same club as did Edward Warwick, the Philadelphia Sketch Club. While I was a member, one of the services I contributed was to write biographies of past members. (Only deceased members because they demonstrated a courteous restraint and never criticized my biographies.) Edward was known as Ned by the other members.

Ned’s only son was also named Edward, Edward Worthington Warwick, and was also a member of the Club. The younger Edward was known as Ted. Ned was dead and Ted was already an old man who rarely came down to the clubhouse when I joined. So, Ms Keogh and I ventured out to the retirement home where he lived with his wife Virginia. The afternoon was spent querying him about his father for the biography I was writing, but we talked about much else as well.

The piece was written and published in the Club’s newsletter. As usual, Ned had nothing critical to say about it, but Ted did have something to say. He was enthusiastic about what I wrote and sent me his father’s block print as a gift.

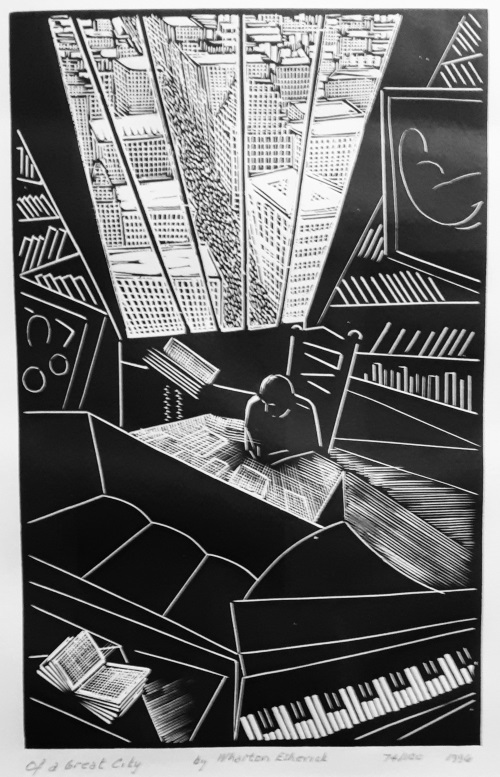

The third piece is a woodblock print, this one by Wharton Esherick (1877-1970), a woodworker extraordinaire. His principal work was sculpture, but he also made furniture and my woodblock print. My print is actually a re-strike titled “Of a Great City”. At its center is a man writing at his desk. The room around him looks like a set from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Surrounding the writer are rows of books, large paintings, and a piano with incorrect black keys, so for all his many talents, I’m guessing Esherick wasn’t a musician. Prominent behind and above the writer is a large window looking down into a city that, judging by its buildings and traffic, could only be Manhattan.

I knew nothing about Esherick until Ms Keogh made the appointment and had me drive us to visit his studio, now converted into a museum. It was sublime. The rooms flowed about you; nowhere was there a straight line. It was as if the rooms and the furnishings had been grown inside a tree by a wizard, like Tolkien’s Rhosgobel where Radagast lived. As a memento of our visit, Ms Keogh purchased for me the woodblock print from the museum’s shop. It now hangs beside my desk and next to the window that looks down into the heart of Cardiff.

The art in my apartment serves as a continual catalyst for immediate admiration and personal memories. Similarly, the Greek, Roman, and Byzantine antiquities of Palmyra can be immediately appreciated and have locked in them humanity’s memories. Khaled al-Asaad, Syrian archaeologist and the head of antiquities for the ancient city of Palmyra, evacuated the city’s museum when it became apparent that ISIS/ISIL would conquer the city. ISIS/ISIL captured and tortured the old man, in his eighties, to make him reveal where the artifacts were hidden, so they could be sold or destroyed. They failed to unlock those secrets from this savior of culture and history; he was publicly beheaded and the headless body hung from a traffic light.

![]()

Mr Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about

the events and concerns of his life. If you've any

comments or suggestions, he would be pleased to hear

from you.

Selected Suburban Soliloquies, the best of Mr Bentzman's earlier series of Snakeskin essays, is available as a book or as an ebook, from Amazon and elsewhere.