|

97. Beethoven 250 Begins

Where does music come from? I play music to set my mood. I sit at the keyboard and compose this essay while listening to a recording of Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony in F Major, the “Pastorale”, Opus 68, transcribed for piano by Franz Liszt and performed by Glenn Gould, who hums on occasion as he plays. Tonight, music comes from two tiny Advent speakers plugged into my laptop.

When did I first hear Beethoven’s Sixth? My mother took me to see a “cartoon”, Walt Disney’s Fantasia. How old was I? Five? That first time is in the foggy past of the 1950s when we still lived in an apartment in the Bronx. I have seen Fantasia many times since.

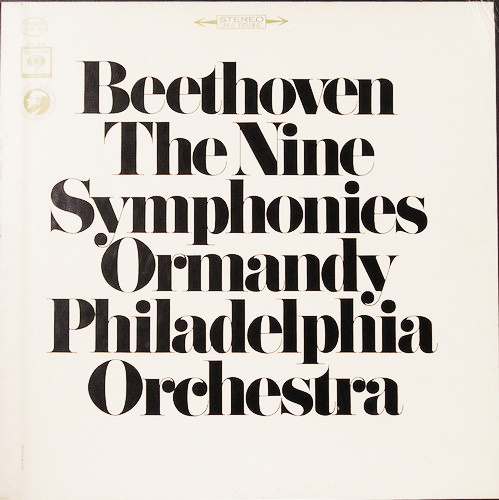

Sometimes your favorite rendition of a piece is simply the first time you hear it, yet it wasn’t Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra that became the epitome against which all other renditions would be compared. At my urging, when I was around twelve, my father purchased for me all nine Beethoven symphonies in a single box set issued by Columbia Records. Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra would to my young mind be the single best interpreter of those symphonies for years to come.

I no longer have any LP vinyl recordings, but I remember the bold black words centered in a column on the white box:

In time my collection of the Sixth grew to include Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berliner Philharmoniker [a disappointment], Georg Solti and Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and The London Classical Players conducted by Roger Norrington with a performance on period musical instruments. None of them have accompanied me to Wales. I gave away my CD collection while still in the United States, except for those out of print and irreplaceable. I left behind my Onkyo amplifier, receiver, and multi-disc player, and a pair of Magneplanar MG 1.5 planar-magnetic speakers. I told myself I was growing old and my hearing less sensitive, not to mention the curse of tinnitus.

This year is the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. Cardiff is celebrating with performances throughout the year by different orchestras in various concert halls. The celebration began on Sunday, 19th January, at Saint David’s Hall, and it began with a performance of the Sixth Symphony.

This concert was a recreation of the historic concert of 22nd December 1808 in Vienna. Beethoven, in financial straits, put together a four hour concert of his music, all new pieces being premiered except for one. Two symphonies were presented for the first time, the Sixth and the Fifth, in that order. It was a benefit concert to benefit himself. It probably was not as good as the concert I attended in Cardiff.

At that original concert Beethoven himself conducted and Beethoven himself played the piano. The performances suffered from the difficulty of procuring enough talented musicians due to a competing concert across town to raise money for the widows and orphans of musicians. Beethoven’s concert also suffered from a lack of rehearsals, unfinished music revised at the very last moment, and an insulted soprano who walked out leaving a stage-frightened novice to sing Ah! perfido, the only piece not being premiered. We also have many chilling accounts that the theater was very cold. The concert was four hours long.

Theater an der Wien was only seven years old. The theater had already seen the premieres of Beethoven's Second Symphony (1803) and Third "Eroica" Symphony (1805). Beethoven had lived in that theater while composing his opera Fidelio.

Because the concert was four hours long, they split the Cardiff performance into two parts, each with a different orchestra and conductor and soloists. The first part was the Welsh National Opera Orchestra conducted by Carlo Rizzi. The second half was the BBC National Orchestra of Wales conducted by Jaime Martín. The BBC National Chorus of Wales performed in both parts. We were provided a 90 minute interval between the two parts so people could step out and grab a meal. In keeping with the original concert, it began with Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony.

The WNO Orchestra presented themselves uniformly decked in typical black outfits. This time, a dash of color had been added. The men sported red pocket handkerchiefs in their jackets and some wore red ties. The women were adorned with a single red peony made of silk. Some wore it in their hair and others on their gowns, and in one case she displayed the peony on her double bass. I noted a violinist who had ruby red slippers poking out from her long skirt.

Rian Evans wrote in her Guardian review the following day, “…Carlo Rizzi conducting a storm in its thunderous 4th movement…”. The maestro led his musicians with the sweep of graceful arms and he bounced on his feet with enthusiasm. It contributed to my enthusiasm and I couldn’t close my eyes, but watched and smiled and wondered if it was ever this good before?

The entire evening was a fantastic success. There were no weak performances. To my uneducated ears, the whole thing was exceptional. Maestro Martín later conducting the Fifth was no slouch. I am confident that this concert was superior to the error-plagued and short-on-talent concert of 1808. Nor was it cold inside our concert hall.

Why is it a particular collection of noises in a specific arrangement can extract wordless emotions? We chant our ancient religious texts. We sing our prehistoric epics. We remember words cast as lyrics or in the song of poetry better than the words of dry speech. Music binds all of humanity without translation, a universal language. Which came first, music or language? Beethoven’s walk in the woods transformed birdsong and thunderstorm, communicated to us by flutes, oboes, violins, kettle drums. We don’t need music for our preservation. It has no substance to keep us fed, sheltered, or warmed. Why does this miracle exist?

![]()

Mr Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about

the events and concerns of his life. If you've any

comments or suggestions, he would be pleased to hear from you.

You can find his

several books at www.Bentzman.com.

Enshrined

Inside Me, his second collection of

essays, is now available to purchase.