|

98. Statuesque

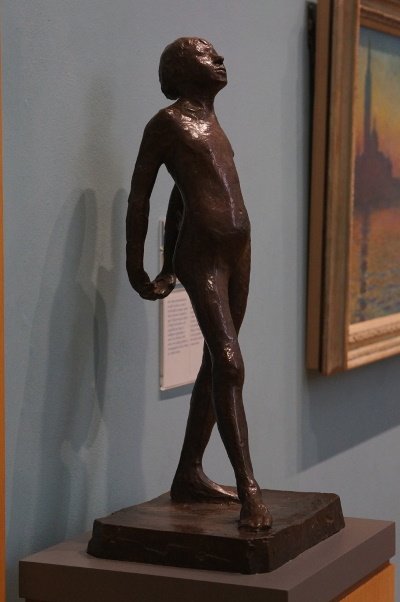

I was surprised to find an unfamiliar version of

Degas’s bronze of the little dancer at the National

Museum Cardiff. This version has Marie van Goethem

naked and waiting to be clothed. Marie left her

working-class parents in Belgium and came to Paris to

learn ballet. She presents a fourth-position stance.

When the statue was first exhibited, plenty of men

described her as ugly. It was a time when the Paris

ballerinas were often targeted by pedophiles and, from

what I read, Degas was a misogynist. Afterwards, Marie

disappeared from history leaving only the many

versions of her in statues as the last record of her

existence.

In all the previous statues of Marie that I have seen

she is wearing a tutu, a corset, and sometimes a

ribbon in her hair. Those versions came after the one

in Cardiff. This one in Cardiff has not even the same

face.

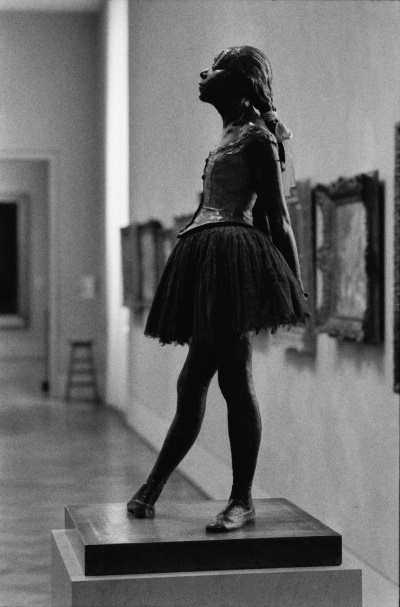

The one I admire is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Degas's La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans (Little

Dancer, Aged Fourteen). That 39-inch bronze exists in

multiple copies displayed in more than two dozen

museums. Each is slightly different, usually the color

of her tutu. She's adorable. There is an expression of

impudence on her face and for that she reminds me of

my friend Stephanie.

I have

known Stephanie since high school. Young men fell in

love with her. My friends fell in love with her. I

never did, but I could see what it was. Slight of

build, she moved with a natural grace. She was

comfortable in her clothes, dressing to a personal

taste that was not dictated by the latest fashion nor

aimed at exciting young men already driven mad by

out-of-control hormones.

Stephanie had contempt for small talk or maybe it was

shyness. She didn’t suffer the superficial, but she

flamed when the subject was art and culture, losing

herself in the esoteric. She was independent and not

one of the girls. Never talking much, but when she did

her few words were interesting. It was never about

herself. Her reluctance to speak made her mysterious.

When we conversed, it felt like we were in a French

film.

Ah, but when I was sixteen and living at home, on my

bedroom wall hung a large black and white poster of

Sophia Loren, the iconic moment when she returns to

the boat, her skimpy clothing soaked and translucent.

The still was from the 1957 film Boy on a Dolphin,

which I never saw and didn’t realize was in color, a

film that also happens to be about a statue. It was

how the ubiquitous culture of my age directed my

instincts, molded my tastes.

Forty-five years ago, I left Ricker College in

Houlton, Maine without completing my education in

order to pursue a romance. I followed my sweetheart

who was also leaving school to return home to Boston.

I cannot say if she was promising a relationship or I

had deluded myself into believing one was forthcoming.

I was young and poisoned by the hormones raging

through my body. She was a bombshell, sexually

irresistible. Nothing came of it and I found myself

living in Brookline, adjacent to Boston, and working

as a clerk for the Social Security Administration. I

went to the museums a lot.

On one visit to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, an

easy stroll across Riverway Park and the Muddy River,

I found a small bronze figure of a standing woman

wrapped in a cloak. However, she was lifting the cloak

open to reveal her demure face and pert breasts. The

title of the piece was “Nature Unveiling Herself

Before Science”, a 23-inch bronze by Louis-Ernest

Barrias. Nature was attractive. I lusted to own the

piece. I thought the allegory very clever at the time.

Recalling the statuette now causes me to laugh. Only a

horny man would credit the erotic pose as an allegory

to the pursuit of science. The statue was not

describing a passion for science. It was, if anything,

a distraction from the pursuit of science. The

figurine will not hold the same symbolism for the

woman scientist, unless she is a lesbian. Could there

be another bronze with the same title showing instead

the figure of a young man drawing apart his cloak to

reveal his penis and calling it “Nature Unveiling

Himself Before Science”?

I have become the old man, yet my eyes still lust at

the sight of nubile women. Long ago, my youthful

passions for women like Sophia Loren and Raquel Welch

with time gave way to more sophisticated tastes,

switching my allegiance to Lauren Bacall, Greta Garbo,

and Audrey Hepburn. I do not say Audrey Hepburn

without sighing.

Then I met Ms Keogh. She would become my cherished

companion. In a few days, the seventh of March, it

will be our 33rd wedding anniversary - had she lived.

37 years ago, on a warm summer night, I rode Amtrak’s

Night Owl coming up from New York City to court her.

Because Ms Keogh lived in Canton, a suburb of Boston,

I used to get off the train at Route 128, a stop

before Boston. That summer morning, she was not there

to meet me. I had a long wait before her appearance.

Further south, she came out of the woods that lined

the track and danced, balancing on the rail in a

flowing long skirt, a slender nymph. She was the

“Spirit of Ecstasy” on the hood of a Rolls-Royce.

![]()

Mr Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about

the events and concerns of his life. If you've any

comments or suggestions, he would be pleased to hear from you.

You can find his

several books at www.Bentzman.com.

Enshrined

Inside Me, his second collection of

essays, is now available to purchase.