|

From the Night Factory

I never took the time to meet Jaimes Alsop, though he had promised to stand me a beer and was even living on the East Coast for several years. When The Alsop Review was still young, Jaimes invited me to submit works. It was about the same time that I was also invited to write a column for Snakeskin.

Jaimes took to Buddhism, became a vegetarian, and moved back to his beloved California. Then, with shocking suddenness, he became sick and it was discovered that he was in the late stages of ALS. On 23rd June, Jaimes Alsop died in a San Francisco hospice.

This essay first appeared in The Alsop Review, a while ago, and is reprinted here with thoughts of Jaimes.

6. Something To Write About

I awoke in pitch blackness with the sound of an explosion reverberating in my ears. It was never the explosion itself, of which I have no recollection, but the ringing aftermath. There was also the sound of the explosion echoing from distant mountains, like rolling thunder. My very first thought was that the house next door must have blown up. I was used to streetlights or starlight seeping through curtains and never before experienced darkness as in Japan, where windows are shuttered with sliding panels of wood called amado. The room began to rumble and shake vigorously. From deep inside the earth came a grumbling and I was unable to climb out of my futon to stand or run. A revisionist memory would declare it was due to the shaking, but it might have been my sleepy daze, or paralysis from fear? I could envision the thin walls of this traditional Japanese house collapsing, the heavy roof caving in on me. In another moment the grumbling moved away, the giant monster boring deep into the ground. We were safe.

Was it an earthquake? Then why the explosion? I also considered a nearby tanker trunk having exploded, interpreting the event to situations plausible to my suburban U.S. experience. Still there was the definite earthquake. Maybe it was an eruption - but so suddenly, without warning, and wouldn't it continue growling as it spewed lava and ash? Although the floor and house were still, I had not yet decided to get off my futon. What if there was a lava flow? It wouldn't reach us, I decided, there being a slight valley between us and Asama-yama. Still, there could be poisonous gas? I decided to check.

Leaving my room, turning on lights, I called to Kazuko, who occupied a different room in the same house. There was no answer from her room. I concluded that it had been an earthquake, a small one that Kazuko wouldn't even wake for, being Japanese and habituated to earthquakes. As for the explosion, I began to even doubt there was one. It had happened in my sleep, was already a memory when I awoke. The reverberation in my ears, maybe it was just the first stages of the earthquake. This was denial arising from inexperience. It was then that Kazuko called out from her room, "Bruce?"

"Yes?"

"Did you hear anything?" She didn't seem very upset.

"Just one of your earthquakes," I suggested.

I opened the front door and checked the volcano. It was too dark and I couldn't even see a star in what I imagined to be an overcast sky. I could see nothing of Mount Asama; except, there were a few bright lights on what would have been the side of Asama facing us. I tried to focus on them, wondering if they were other houses. That there could be homes on a volcano didn't seem implausible to someone who knew nothing about such things. I was trying to relate what I was seeing to my limited experience of Pennsylvania, which has plenty of homes on the sides of mountains, but I know of no volcanoes in the Commonwealth. Deciding they were spotlights, imagining research stations on Mount Asama, or something of that ilk, I went back to bed, refusing to believe I could be in danger, or even have reason for concern, never suspecting that a prayer had been answered. In fact those lights were the glow of molten rocks that Asama had just spewed.

Karuizawa is three or four hours driving northwest of Tokyo, in what the Japanese regard as their Alps. Kazuko's parents had a summer house there. In the Spring of 1983, my patron, a Japanese woman who thought I held promise as a poet, took me to Japan for the experience. I had never before traveled overseas. While I was there, my ex-wife, Kazuko, was gracious enough to host my visit, even though I was carrying at the time our divorce papers for her to sign. (To this day Kazuko remains among my dearest friends.) Although it was still too early in the season, because I was overeager to see something of Nature, having seen nothing but Japan's overpopulated cities, Kazuko's parents arranged to have their summer house opened. Kazuko borrowed her brother's car and we were off to the mountains.

During my three weeks in Japan it mostly rained or threatened to rain. I never once saw Fuji-yama, meaning Mount Fuji. Many Japanese refer to this famous dormant volcano with a more respectful nickname, Fuji-san, meaning Mister Fuji. Though most of my time was spent in Tokyo, Fuji-san was always concealed by rain clouds when I was in its vicinity.

The mountains of Japan that I saw possessed no majesty; I had briefly lived in Boulder, Colorado in a house at the foot of the Rocky Mountains. The mountains of Japan that I saw were not massive and pyramid shaped, they did not rise as often above the timberline. Instead, they curled and folded, looking like there were children playing under green blankets, rising to their knees and about to tumble over. These were the mountains found in Ukiyo prints, elongated vertically and undulating precariously. They were arrayed with knotty pines; these twisted evergreens unrelenting in their occupation, they made inroads onto the flying buttresses of rock that supported ledges. It was enthralling beauty. It became easy to understand how this country was so hard to unify when I saw the barriers that divided it. I could see there was room enough for a million hermit monks to be concealed in the nooks and crannies of this terrain. Many poets must have gotten lost awhile in these mountains, before these mountains were caught in a net of roadways and tamed by the maps. Kazuko, for my amusement, purposely took the scenic winding roads about the mountains groping claws.

The summer home was in a resort community where each separately contracted house is unique in design, surrounded by forest, and given ample property. Their summer home was high up on a hill adjacent to Mount Asama. You could clearly see Mount Asama towering above. It was a flat cone shaped mountain capped with snow. A small thread of smoke rose from the pinnacle and blended into the low overcast, hard to notice, yet was the proof that Mount Asama is an active volcano.

We dropped our bags at the summer house and climbed back into her brother's car. Kazuko drove us along the meandering roads that circumnavigated Asama and brought us to its other side. Here Asama-yama was a treeless landscape. Paved trails had to be carved out of the ragged lava surface. Huge lumps jutted sharply in all directions. Had the smooth paths not been made, it would have taken hours to lumber across this difficult terrain. Every several yards the public was provided with concrete shelters, short open-ended pipes with benches placed inside, reminders that the volcano was active. Looking about me provoked my imagination. I tried to conceive this field of boulders fluid and all aglow. The path lead us to a temple or shrine; I'm no longer clear as to which and here my notes are hazy. It was another chance to pray.

During my visit to Japan, I made a habit of praying in the manner of the Japanese at most every shrine or temple we visited. They are everywhere, just like Christian churches are everywhere here in my own nation, but the U.S. churches are far from being as beautiful. Although I am an Atheist, unaccustomed to prayer, I nevertheless made it my practice while in Japan, thinking it would be respectful, and that it would provide me some insight as to the country's culture. I wanted as much as possible to immerse myself in the Japanese experience. The day before the eruption, I did just that.

Suspended below a small roof was a bronze bell. I threw my coin into the box and grabbed a rope that was joined to a horizontal post suspended over my head. I swung the post and sent it ramming into the adjacent bell. Bong!!! The tone was rich and long-lasting, creating a chasm into another dimension, a deep tunnel down which the sound of the bell rushed until it was too far away to be heard, but one can believe it went on forever. The harder I listened, the longer I could hear the enduring bong. When the sound of the bell was out of earshot, having gained the attention of the spirit of Mount Asama, I prayed.

To the spirit of Mount Asama I prayed for an eruption. Nothing drastic, just a small eruption which shouldn't hurt anybody. I especially wanted to survive the experience, telling Asama-san that I was an insignificant poet on vacation, looking for inspiration, something to write about. I thought nothing more of it. That evening Kazuko and I had dinner in downtown Karuizawa and went home to the family's summer house.

The strange morning following the eruption, I awoke in a rural environment and there were none of the expected bird songs. Kazuko greeted me with, "was there an earthquake last night?" I suggested it was either an earthquake or an eruption. "Something's happened, Bruce. Can you hear all the airplanes and helicopters?" I could. The amado was opened and through the windows of the house facing away from Mount Asama we saw a grouse running in the underbrush. Kazuko turned on the television to learn what if any news.

"Would anyone call us here if we were being threatened by Mount Asama? Would they know we were here, this being early in the season for occupants?" I looked out the door. Mount Asama was black and gray under yet another cloudy sky. Then I noticed the tan ash on her brother's car parked in the driveway. A very fine ash, it covered only a third of the car's smooth, clean surface; and I announced to Kazuko, "there was definitely an eruption. The car is covered with ash." This was soon followed by the news report for which Kazuko had been waiting. There had been an unpredicted eruption at 1:59 a.m. of medium size that threw ash and molten rocks. Lava rose in the crater, but did not crest the rim. Mount Asama had blasted in a northerly direction sparing us.

Kazuko had called her parents to tell them we were all right. They had not wanted to call us, not wishing to wake us if we were sleeping late.

At last admitting to myself that Mount Asama had erupted, my imagination extended the volcano's potential for devastation until I had convinced myself a further eruption engulfing the entire mountain was imminent. I was eager to escape Karuizawa. Kazuko, on the other hand, was eager to drive to the other side of the volcano, where we had been the day before, and be a witness to whatever damage could be found. I presented my fears as practical concerns. Kazuko rebutted with a knowledge of Asama's history, whose activity is rarely extensive and never quick. She added to this point how it was thoroughly unreasonable to pass up this experience, so very, very rare; especially for me, a poet. She was absolutely correct and I had to admire her courage. I agreed we should go, but, dear reader, only because I could not have my ex-wife thinking I am a coward.

The far side of the volcano had been transformed into another world, thoroughly different from the day before, an unreal illusion. Gray ash covered every detail leaving no trace of original color. Every leaf in the forest was gray. Some god used his masterful craft to carve from a single gray element an exacting copy of a terrestrial scene. Not a single detail was missed, even to a different shade of gray for the veins of the leaves. As the few cars passed going in the opposite direction, they launched trailing billows of smoky ash in their wake. Passing cars momentarily blinded us, and I turned and discovered we had been doing the same. We had to stop the car and wait for the ash to again settle. Tractors had plowed parts of the road. A man was shoveling the ash off the roof of his house. He wore a bandanna over his mouth and nose. It was a chillingly unnormal world.

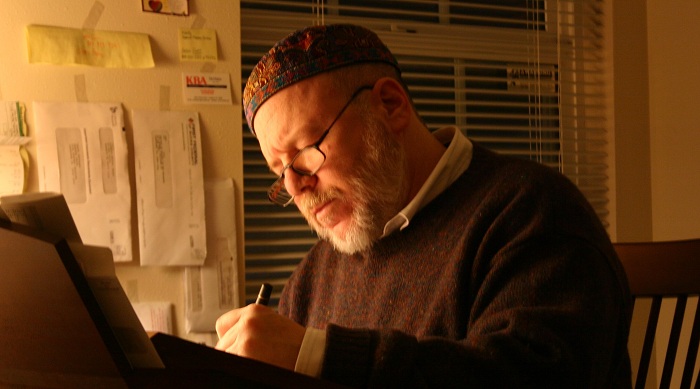

"Don't you remember, Bruce, it was snowcapped." She was right. There was no snow left on this side of the mountain, or more accurately, no snow visible. At first, I thought it had melted away, but the eruption was too sudden for that and probably just covered the snow under a deep ash. I sat on a bench with Asama-yama behind me so that she could snap a picture. That picture, proof of my visit, is sown into my notebook. I also have a stamp, placed there the day before the eruption by a Buddhist monk or novice. It shows I visited that holy site, and in elaborate calligraphy, the robed fellow wrote the date, not that I can now translate it.

Kazuko pointed out what I, at first, mistook for a cloud stuck to the top of Mount Asama. It was a thick gaseous plume blending into the overcast.

Courageous Kazuko wanted to drive to the museum halfway up Mount Asama. Outrageous Kazuko wanted to drive to the very top and look in. This wuss, yours truly, wanted a quick return to the safety of Tokyo, wondering if even that would be distant enough from a volcano that might unexpectedly exceed the dimensions of Krakatau. I was ready to abandon my vacation before Japan exploded in two and both halves sunk into the sea. As before, I concealed my fear and once more preached caution, and once again she insisted. She had the wheel of the car. I swallowed my fear, but had to wonder if my ex-wife intended this for a double suicide - oh why couldn't I have just mailed her the divorce papers?

As earlier I had to conceal my terror, now I had to conceal my joy. The road to the museum had been closed and guards employed to turn the curious away. Brave Kazuko was genuinely disappointed. She even tried arguing with the uniformed guard. I had been married to one of those extremely few Japanese women who do not respect authority as is otherwise typical for her generation.

One can ask little more of a vacation than to comfortably survive an event and to come away with an adventure worth telling. Since my visit to Asama-yama, the volcano will always occupy my heart and mind. This unbeliever, this skeptical Atheist, who will tell you the volcano's answer to his prayer was nothing more than a coincidence, nevertheless finds occasional comfort talking aloud to Asama-san, even though Mount Asama is now thousands of miles beyond the reach of my voice. Mind you, dear reader, I avoid prayers to Asama-san, but just talk casually, now that we are friends. And here I shall conclude this true story with a reminder to the reader to keep in mind the old adage, be careful what you pray for, it might just come true.

Mr

Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about the events and

concerns of his life. If you've any comments or suggestions, he

would be pleased to hear from you.

Mr Bentzman's

collection of poems "Atheist Grace" is

available from Amazon, as are "The Short Stories

of B.H.Bentzman"