|

From the Night Factory

20. William H. Campbell, artist.

As a member of the Philadelphia Sketch Club, I was enlisted to compose short biographies of some of the more illustrious dead members. It was a matter of Club pride that many famous and forgotten artists had smoked, drank, eaten, and argued in those confining rooms. They also sang and danced. They performed farces and found other excuses to wear costumes. They competed at games and art – especially art. Most importantly, they lent each other support and advanced art in the community.

Because of my researches, I was advised to make the acquaintance of William H. Campbell, a renowned Philadelphia artist and, at the time, one of the Club’s oldest members with one of the longest memberships, eventually becoming both the de facto oldest and longest. The Philadelphia Sketch Club has a history going back to 1860, and Bill joined in 1939, had been hanging around the Club even longer. He had been a part of the Club for half the Club’s entire history. Despite extreme old age, Bill's memory was uncanny.

So began my regular visit to Bill. Age had impeded his visits to the Club, so we would meet at his home, a townhouse in Philadelphia. It was a modern structure near the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, a six minute walk to the Rodin Museum, perhaps fifteen minutes up the long staircase to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The first floor was his garage with a work and storage room in the back. To enter the living space proper, you climb a long narrow set of stairs. On the second floor was his kitchen in the back and a large living room, two stories tall with a large window facing east. The living room served as his studio and here we had our talks sitting across from each other at a long table. On the walls were several of his large abstracts.

That he befriended me was a surprise. Bill was persnickety and demanding, eager to employ anyone who entered his life, yet highly critical, impatient when things were not done exactly to his preference. He was quickly annoyed when promises were not kept or when others proved to have memories inferior to his own. I firmly established at the beginning that I was unreliable. I informed him outright that I could not to be trusted to remember things or to accomplish things on time, which is why I avoided making any commitments. I don’t think Bill, forever the perfectionist, at first believed me; rather, he thought I was being humble. It didn’t take me long to convince him. I laughed at his displays of aggravation and reminded him, he had been warned. He came around to accepting me as I am; for all my faults I was at least honest.

At the beginning of our acquaintance, I had to admire the care of his appearance. A small and slender man, he was never slovenly, but always immaculately dressed, his clothes clean and ironed, his thick crop of white hair combed, and his jaw shaved smooth.

We argued and we gossiped. Our conversations went beyond the subject of the biography I happened to be working on. We discussed the big questions; life, death, God, purpose, fears, art; nothing was taboo. We discussed his death, yet we did not talk much about his health. That was because it was a subject that bored me. Old people are too often inclined to elaborate on their personal medical problems. Sure, it is possible for me to feel sad for the sufferer, but such talk derails every other conversation as it begins to dominate. Bill respected this and rarely discussed his health at length. More and more we talked about his life. He talked lovingly about his mother.

It was his mother who introduced him to art, took him as a child of five and six to the museums that first inspired him. After visiting a museum or exhibit, his mother would take them to the Crystal Tea Room at Wanamaker’s where Bill always ordered the chicken croquettes with cream peas and mashed potatoes. And Bill drew. Every drawing that Bill rendered, his mother would tape to the door of the kitchen pantry.

My visits to Bill were not as frequent as my letters. At first he wrote as often as I wrote to him, and I have a folder four inches thick with his letters. In the last few years of his life, about the same time he sold his car, it became harder for him to write. He preferred responding to each of my letters with a phone call.

As 2011 drew to a close, Bill began experiencing new medical issues. When the new year of 2012 began, he told me he didn’t expect to live out the year. I could see he was now aging quickly. His features were changing dramatically and at every visit he looked different. He became disheveled and swaths of facial hairs had been missed when shaving, places under his chin he either could not see or could not reach with his razor. His shirts hung from the sharp ridges of his shoulders. His cheeks, nose, ears had all grown edges. His skin developed a patchwork of sores and bruises that weren’t healing. Still, he had his full head of white hair neatly combed.

For him the days grew shorter. It took longer to get up and get dressed. He tired sooner and went to bed earlier. He was applying all his conscious hours to organizing the ephemera of his life and of the people he knew, exactingly organized and collected into boxes. With every story he pulled out a box to illustrate the past with catalogues, newspaper clipping, and magazine articles. At work on his legacy, he had no time for dying.

Just when I thought there would be no more letters for me from Bill, there was one last letter he handed to me during a visit. This was in June of this year, 2012. It was a response to a question I had posed two months earlier; if you could sit down to two dinners for a long conversation with first four dead people and then four living people, who would they be? Despite the professed difficulty he had writing, he managed a lengthy response in an admittedly squiggly hand. “Your question about a Live and Dead dinner party for four people, has been on my mind. I have made endless notes and changes.”

Bill Campbell’s list of four dead dinner guests were the artist Earl Horter, Bill’s favorite teacher; Mrs. Joseph Pennell, who Bill claimed was a far better writer than her husband the etcher; Lyman Saÿen, who Bill declared a creative genius; and Sergei Diaghilev, founder and impresario of the Ballets Russes.

Then there was Bill’s list of four living dinner guests: the artist Paul Klienbordt (AKA Pablo Davis), one of Bill’s classmate with whom he graduated art school in 1937; Philadelphia artist and dear friend, Francis Cortland Tucker, for whom Bill yet had many questions; the composer Arvo Pärt; and lastly, quite to my astonishment, he listed me, “Bruce Bentzman is a free spirit that I enjoy knowing. He would be an excellent interlocutor for this affair, if he is awake at the time.”

June, July, then came August, each much heavier and weighing Bill down. In the beginning of August, I visited Bill and he had not bothered to come downstairs to the living room on the second floor to meet me. Instead, he had me climb to the third story where I found him dressed, but still sitting on the corner of his bed. He apologized, saying he had found it very difficult to get up that morning, but this was two o’clock in the afternoon. I was of the impression he was about to call off my visit and send me home, but I immediately engaged him in conversation and as he talked, he gained energy.

The room we occupied was his office. Bill had moved down from his fourth floor bedroom to live on the third and second floors only. The staircases were becoming insurmountable for his 96 years. He was now receiving regular visits from hospice care.

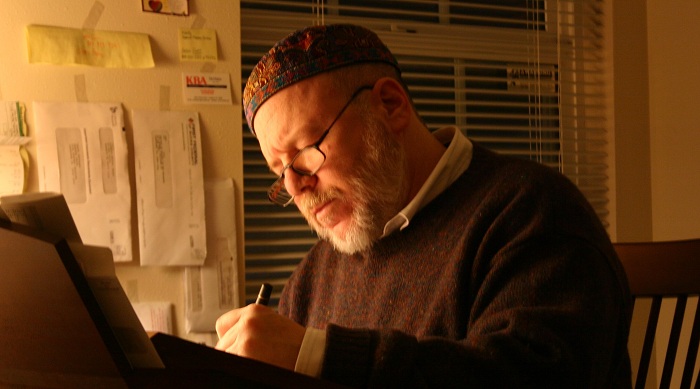

Bill moved to his desk and I sat beside him as he engaged me in a project. He wanted me to update and correct a sheet filled with his career achievements and make it more presentable. Then, on the back of the sheet, he wanted me to compose his biography. He emphasized that it was to all be restricted to a single sheet for him to use, to give away, at exhibitions of his work. “I want you to write in the style of the essays you used to do for the Philadelphia Sketch Club Portfolio.”

“But you know,” I reminded him, “I made it a point to only write about dead Club members, that’s how I avoided complaints. I never wrote about the living.”

“Well, I’m almost dead.”

“In that case, maybe I could fill half the page.”

“Sure, you could put ellipsis at the end,” and he punctuated the air with his finger, dot-dot-dot.

By the end of our conversation, he felt invigorated and strong enough to move downstairs to the second floor. I did write the piece, finishing it in September. I have included it at the end of this essay.

The 25th August, I called Bill when I woke to finalize the plan for me to come visit the following day, which was a Sunday. I wanted to discuss further the story of his life, the things I remember him telling me, nailing down the approximate dates, et cetera. He called off the visit. He explained he had fallen the day before. He had been running an hour and a half late going to bed. He went to the kitchen to get a container of ice, which he intended to keep by his bed. He didn’t like the Schuylkill punch, the local denigration for Philadelphia’s tap water, especially because it never got cool coming out of his pipes on those hot summer days. So he kept a container of ice made from filtered water, which melted overnight and was then a cool drink in the morning when he woke. Carrying the ice proved awkward. As he began to make his way to the next floor where he slept, at the very first step he had trouble and fell, injuring himself. For the time being, he didn’t want me visiting.

He again invited me to visit and I returned 8th of September. His movements were delicate and careful. He slowly pulled a handkerchief to his nose and gently blew into it. His left arm was wrapped in bandages from having fallen two weeks before. He was also wearing a catheter and a bag collecting urine. He had been diagnosed with liver cancer.

During this visit, he made a meal of a half inch slice of challah cut into three strips onto which he had spread apricot preserves. He was over an hour eating the first two strips and was just beginning the third when I departed.

The 14th of September was Bill's 97th birthday. His health was rapidly declining at every visit. He now had hospice care at home. Because he lived in a townhouse, they had restricted him to one floor. They had delivered a hospital bed to his living room.

By the end of September, Bill was living at Penn Wissahickon Hospice at Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia. Only now, at this very late time in his life, did I observe the first indications of mental decay and felt it remarkable that it should only appear at the last. His speech was much slower and he was having difficulty with word choice. To my surprise, he was missing his lower teeth. I learned for the first time that he had dentures, only because for the first time he took them out in my presence. He laughed at my surprise. His shock of hair was cut shorter than ever. His hearing loss was now very severe, so I let him do most of the talking. He wandered down distant memories, launched by unexpected associations to my questions. In these last days of his life, he was remembering his daughter, a suicide. He told me, “I never before could understand why she did it. I understand now.” He told me he understood how life could be so difficult, painful, tiring, and now he wanted to die, too.

He did not live much longer. At the next visit, there was a clear tube feeding oxygen to his nostrils. The pump behind his bed sounded like an idling diesel train; hum, clunk-clunk, hum, clunk-clunk. He sat up in bed without book or television, even at this late stage he was busy making notes about his life, actively working at his legacy. I would pull the chair closer to his bed so he could hear me, situating myself next to the plastic bag collecting his urine. I understood why he was unfolding so many old memories to me; he was reviewing them, keeping who he was alive, because we are our memories. I realized he was having trouble with his short-term memory. This was new.

In October, Bill was briefly moved back into his townhouse. He wanted to die at home, surrounded by reminders of who he was. He was there only a few days and started to become disoriented, thinking that he was being robbed and that the hospice care was a scam. He tried calling the police and the fire company. They moved him back into the hospice center. We spoke on the phone. We discussed when I should come and visit. First he said it’s not a good time, but then he said I should hurry – I knew what he was trying to say, without saying it directly, that he didn’t think he had much time.

His life persisted deep into October. The painting in his hospice room was now replaced with one of his own abstracts. This was something I had wanted to do earlier. His cousin Thelma had the same idea. Unlike me, she didn’t ask him, but acted. I inquired of Bill how he knew for certain the piece wasn’t hanging upside-down? He laughed and said, by how it was wired on the back.

His nose and ears seemed larger than I remembered them. I decided it was his skin shrinking, tightly wrapping his skull. There were more unhealed scabs. His long fingers were warping. He tried giving me an assignment, wanting to give me a list of all the people to whom he wanted me to send the short biography I had written, anybody who even remotely knew him. I said I would discuss it the next time I visited, that I was making no promises. There was no next time.

30th October 2012, Mischief Night, Hurricane Sandy stomped on Philadelphia, and the next day, the 31st, William H. Campbell died.

WILLIAM H. CAMPBELL - ARTIST There was no epiphany that launched William H. Campbell into his career as an artist. As best as he can remember, he has always been. While his father took him to see sports, such as the Frankford Yellow Jackets, winners of the 1926 NFL Championship, his mother cultivated his love of art. Starting in 1920, she would take him regularly to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts to see the Annual shows, a long journey on a meandering trolley before the Frankford el was installed. Born in Philadelphia on the 14th September 1915, it is also Philadelphia which gave him his formal art education, starting when he was 9-years-old at La France Art Institute. During the 1930s in what has now become the University of the Arts, he studied under Gertrude Schell, Thornton Oakley, and Alexey Brodovitch. There was also one summer excursion in 1935 to Rockport, Massachusetts where Campbell received training from Earl Horter, an exceptional teacher and role model, who awakened Campbell’s interest in abstract art. Campbell would eventually become known as the Grandfather of Philadelphia’s Abstract Art Movement, yet he continued to work in both representational and abstract paintings, even as he labored in long careers as an illustrator, designer, teacher, and art director. Even now, the gouaches he painted of Autocar trucks, produced while a commissioned artist employed at Grey & Rodgers of Philadelphia in the 1940s, have been become a sensation on the internet, with the Autocar magazine advertisements having become collectibles. He did not serve in World War Two, due to a childhood fall on a staircase, an injury that caused him to injure his left arm and shoulder, which did not heal properly. Some of the damage was not detected until he was in high school. After the war there were trips to Mexico in 1947 and to Europe and Great Britain in 1956. Campbell is a charter member of Artists Equity and was President of the Artists Guild from 1951 to 1952. He is listed in Who's Who in American Art and Who's Who in the East. He has been a member of the Philadelphia Sketch Club since 1939. Campbell has curated several exhibitions of local artists. Hundreds of his works can be found in private and public collections. He has also indirectly contributed to the musical arts by co-founding with his wife, Jeanette, and three other couples, The Main Point [1964-1981]. This famous coffeehouse was located in Bryn Mawr and attracted such performers as Joni Mitchell, Stevie Wonder, Arlo Guthrie, Bonnie Raitt, James Taylor, Leonard Cohen, Doc Watson, Tom Rush, Odetta, and Bruce Springsteen, to name a few. In 1970, he moved into his present address because it provided him with facilities for producing bigger canvases and to concentrate on pure abstractions. Today, 97 years after his birth, William Campbell lives and works on his legacy at his home and studio; 552 N. 23rd Street, Philadelphia, PA 19130-3117. |

Mr Bentzman will

continue to report here regularly about the events and

concerns of his life. If you've any comments or

suggestions, he would be pleased to hear from you.

Mr Bentzman's

collection of poems "Atheist Grace" is available from

Amazon, as are "The Short

Stories of B.H.Bentzman"