|

From the Night Factory

26. A Gift for the Nakashima Reading Room

When I was attending at Bucks County Community College back in 1971, I came upon a young man who appeared stranded and stressed at the college bus stop. “Is anything wrong?” I asked. He had missed his bus and had to get back to Doylestown right away. Doylestown is the county seat of Bucks County, Pennsylvania. I consoled him, told him to not be upset and that I would give him a lift.

As we drove the winding back roads to Doylestown, I asked, “Where in Doylestown should I drop you?”

“The prison.”

I thought he was joking. “Why the prison?”

“I’m a prisoner.”

Thus I learned my passenger was a prisoner released on a special student program and had missed the prison bus that made sure he reached the college and returned. We talked about other things.

We arrived to the entrance of the Bucks County Prison, a massive stonework built in 1885. It looked fortress-like except where the wall was interrupted by the warden’s house with the main gate smack in the center. I watched to make sure he wasn’t locked out. Actually, I expected it was going to be a goof and he would run off in another direction to where he really lived. He didn’t run off. He took himself straight to the giant wood gate and knocked on a smaller door it incorporated. The door was opened by an old man in uniform who greeted the young prisoner with a smile and a laugh. The prisoner waved to me and disappeared behind the heavy door.

Most of the prison has been demolished, but that part of it that formed the warden’s house and some of the wall remains, a historical landmark. Behind it they built a museum in 1988. Ms Keogh, my more significant other, and I became members in that first year and have remained members ever since.

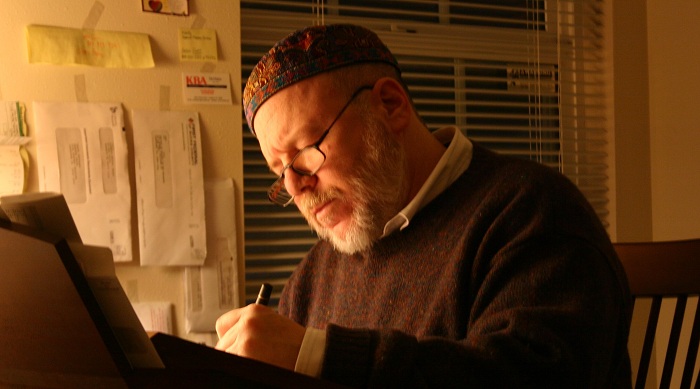

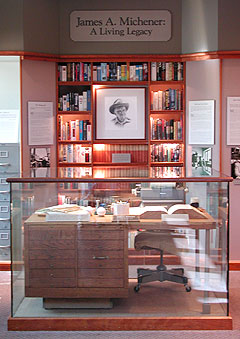

The James A Michener Art Museum was named for Doylestown’s renowned author, a prolific writer of fat books that became bestsellers and movies. They were often epic historical fictions. Despite general expectations, Michener did not employ research assistants, although Random House checked for accuracy his completed manuscripts. The museum has one small room that recreates the office that was in his home where he wrote for thirty-five years.

I once shook Michener’s hand. It was 1962 and I was a child eating with my family at the Five Points Diner when he appeared at our booth and asked for my parents’ vote. He was running for Congress as a Democrat. He lost.

And now we arrive at my subject. In the James A. Michener Art Museum is another room, the Nakashima Reading Room.

George Nakashima was another famous resident and treasure of Bucks County. Artist, architect, woodworker, philosopher; his philosophy revealed itself in the way he chose to live his life, the buildings that formed his compound, and in the furniture he crafted. The furniture reveled in its nature, the wood undisguised, especially in table tops that flowed with the phenomenal grace that revealed contours of the grain. His work was organic.

Born in Spokane, Washington, Nakashima came to Bucks County from an Internment Camp in Idaho during the Second World War. It was in that damn stupid camp that Nakashima made the acquaintance of a traditional artisan who taught Nakashima the art of Japanese woodcraft.

I fell in love with Nakashima’s furniture from the first visit with my parents to his compound in the hilly woods near New Hope. When, years later, I was able to drive, I revisited the Nakashima compound several times. It was always awkward. It wasn’t just his studio, it was also his home. Not having the money to afford his furniture, being young and venturing about his property unchaperoned, I felt like a trespasser, but no one ever challenged my being there.

The last time I visited Nakashima’s studio, I observed him standing under a tree with his gardener. Nakashima was a short, stocky fellow, the gardener was tall and lean, had the appearance of a hippie. All about the lawn were mounds where a mole had been tunneling. Nakashima was asking the gardener’s advice and how much it would cost. The gardener, reluctantly, told Nakashima how difficult and expensive it would be to find and destroy the mole, and that it could take a long time. Just then, as I watched, the mole popped out of the ground at their feet. In the next instant, the gardener had clubbed it with the shovel he was holding. “How about ten bucks?” the gardener said, and they both laughed.

The Nakashima Reading Room at the Museum is dedicated to Nakashima’s talent. The room resembles a traditional Japanese interior with shoji and carpeting that resembles tatami. The center piece is a gorgeous coffee table surrounded by his famous Conoid lounge chairs made from claro walnut. The Conoid chairs rise on only two legs that end with struts. The table is a burly cross section of a tree trunk with a long butterfly joint where the wood had begun to split. The room is not cordoned off and restricted to display only. The joy was to be able to enter the room and sit down. In 1995, the only thing that annoyed me was that they called it a reading room, yet there was nothing in it to read.

In June of 1995, Ms Keogh and I handcrafted a small edition of nine poems telling about my 1983 trip to Japan. The pages were printed on sumi rice paper using my laser printer. It was no simple task. The rice paper was thin and delicate. It was necessary to mount it onto a heavier piece of paper before feeding it into the printer. Ms Keogh then bound the pages in the Japanese manner. We made four books in all; one to keep and three to present to the Nakashima reading room at the James A. Michener Art Museum. Well, “present” is the wrong choice of words. We were determined to avoid rejection and deposit them in the reading room as an act of guerilla art.

We had started out on the first of June to carry the three thin volumes into the museum, but when we arrived, I realized, to my horror, that I had misspelled Michener (spelling it Mitchner). There was no presenting the books that day, not with this all important name misspelled on both the title page and colophon.

For a minute we felt beaten, but then Ms Keogh perked up and insisted we could fix it. Sure of ourselves and the remedy, we rushed home and made repairs. After all, I had saved the manuscript in my computer. We returned to the museum, surreptitiously making our way to the reading room and depositing the books on the coffee table. It was now a proper reading room offering something to read, the promise in the name now fulfilled.

Several days later, I returned and in the solitude of this room read my own gift. They were already showing signs of being worn. To my horror, I found a typographical error in the text. In all three books, I crossed out the wrong letter with my pen and inserted the correct letter. When I informed Ms Keogh, she was not satisfied with the fix. She had me repair the mistake and print a replacement page. Her scheme was to return to the reading room at a later date and, one at a time, steal the books back so she could secretly repair them. When the revised page was ready, we returned to the Nakashima Reading Room to discover all three books missing.

We could only guess what happened to them. Were they stolen, discarded, removed permanently or temporarily? I could think of several reasons why either the museum or Nakashima studio did not approve of what we had done, had not seen my poems as either a gift or compliment. Perhaps they didn’t care for my poetry. Perhaps they thought it arrogant of me to make it seem the museum approved of my work, when in fact they disapproved of my using the museum for purposes of self-promotion. Or maybe, although unlikely, the Nakashima people felt my books were a distraction from the beauty of the coffee table. I didn’t think we would ever know.

Ms Keogh was more upset than me at the disappearance, even though we had both agreed it was ephemeral art and accepted that the books would likely wear out or be stolen. Just their creation was a sufficient accomplishment if only a few people enjoyed them. But it would have been a tragedy if they were merely discarded. I wanted to believe they continued to exist somewhere. They did.

A week and a half later, a letter arrived from Brian Peterson, Curator of Exhibitions at the James A. Michener Art Museum:

| …Three copies of

an elegantly produced and beautifully written

book of poetry mysteriously appeared in our

Nakashima Reading Room a few weeks ago. Our

front desk staff was puzzled and perhaps even a

bit suspicious (who knows what subversive

messages might be hidden in those pristine white

pages), so they promptly removed the offending

items from the room. Eventually they made their way to my desk, and through me to the Director; both of us were impressed by the quality of the work, and intrigued by the rather cryptic presentation. We felt that the book should be returned to the Reading Room, and the gift should be acknowledged…. |

Nakashima died in 1990. His business and craft continued with his daughter, Mira Nakashima-Yarnall, and three months after receiving Mr Peterson’s letter, we received another from Ms Nakashima-Yarnall:

| Brian Petersen,

curator of the James A. Michener Museum, has

brought to my attention the small book of poetry

placed in the Nakashima Room. We are thrilled to know that you were so inspired and hope to meet you sometime! |

We never did meet. The books we made wore out astonishingly quickly and then disappeared altogether, but even the memory feels good. The museum now keeps a couple of reference books about George Nakashima’s life and work on the coffee table for museum-goers.

Mr Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about the events and concerns of his life. If you've any comments or suggestions, he would be pleased to hear from you.

Selected Suburban Soliloquies, the best of Mr Bentzman's earlier series of Snakeskin essays, is available as a book or as an ebook, from Amazon and elsewhere.