|

From the Night Factory

42. A Contemplation of Age and Ancestors

Aging is a chronic illness which creeps up on us until one day we find ourselves defined by who we were and not who we are. Aging is a pointless complaint. For me it is the awareness of the cessation of existence that is most alarming. Still, aging keeps stealing my attention.

I can find an increasing number of disgusting hairs on my ears with the tips of my fingers, even if they are hard to see with old eyes that no longer focus on things which are close. I have this peculiar distaste for ear hairs. Whether the hair is sprouting from the auditory canal or cropping up from the helix or hanging from the lobe, it all disturbs me. Inside the auditory canal they might make sense. How far back in our evolution do we go to find the function of these vestigial hairs about the edges of the auricle? Ms Keogh, my more significant other, is good enough to periodically groom me in that long social tradition of familiarity and bonding among primates, otherwise I attempt to do it myself without the same effectiveness. If I donít consciously restrain myself, I fear I am inclined to pluck the hairs from the ears of acquaintances.

Roger is a Friday night regular at Scrabble. We meet in the back of a bookstore in Trenton. An older gentlemen, more than ten years my senior, he is uncommonly fit for his age and comfortably clean in his appearance. It was with consternation that several Fridays ago, I noticed a single hair, thick and blond, poking straight out from his ear. I could not understand how he was missing it, because he was otherwise trim. I weighed in my mind the extent to which our friendship could be tested and if we were familiar enough that I might take out my handy Swiss Army penknife, unfold the tiny scissors, and snip off that singular and ridiculous hair.

I didnít. Last week, I again saw that awful hair, but this time discovered it was attached to a tiny hearing aid ensconced deep in the canal trying to be invisible. The singular blond hair was the pull by which he could remove his hearing aid.

It is my mother who has me contemplating aging. My mother will be ninety-four in about a month. Her doctor says she can no longer live independently, not without assistance. Ms Keogh and I have been regularly picking her up and taking her to visit the numerous assisted living facilities in the neighborhood. At the start of 2014, my mother was driving every day to where she had to be, going dancing on Thursdays. When she broke her arm falling on the ice in February, she drove herself to the doctor. Here we are in the last days of 2014 and she cannot drive. I must pull her out of the passenger seat into her walker when we visit potential facilities. She has to make hard choices. So do we.

For now, my mother continues to live independently in a small apartment with regular help. In a recent decluttering of storage space, she asked me to discard a thick pile of papers deemed insignificant. Most of it printed on one side, she knew I would recycle it by first inverting the sheets and employing them as scrap paper. I took them home. I discovered the translation of the Memorial Book among the papers my mother was having me discard.

The Memorial Book of Our Family: 1461-1920, was written by my great-grandfather, Rabbi Baruch Cohen, and published in 1920. The book is in Hebrew, which my mother, my older sister, and I cannot read. That book presently resides with my sister. My mother didnít realize that the missing translation, rendered by the now mysterious J.J. Sacks of Boston an unknown number of years ago, was tucked among the papers to be discarded. Itís not like when she threw out the slipcases of my fatherís collection of fine press books to save room on the shelves. Nor is it like when she discarded the leftover bits of gold returned with the rings and bracelets she had had modified to better fit her fingers and wrists. Those mistakes resulted from conscious decisions, but the Memorial Book translation was overlooked, so long lost as to have become a family legend.

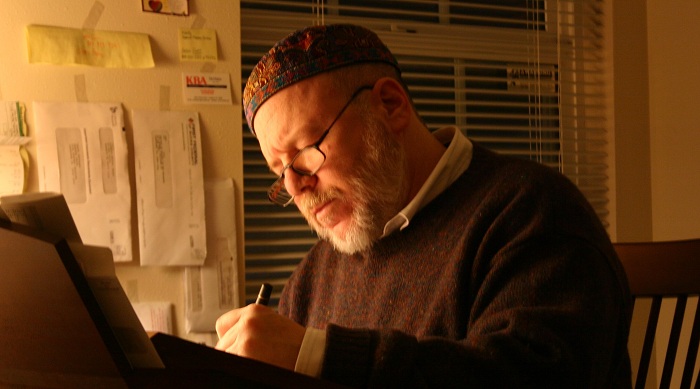

I have started reading the Memorial Book. Either Great-Grandpa Baruchís writing was difficult or the translation was poor. I am confused by the syntax. In corroborating the history with the wealth of material available on the internet, there is the headachy deciphering of ancestors using different names multiplied by variant spellings. I am trying to simplify the story of my motherís family, copying out the generations into a chart, twenty generations in all if extended to me. It should be nice if I can complete it in time for her birthday. I am still having difficulty making sense of the middle generations. Sorting the connections across the generations of the seventeenth century remains teasingly just out of reach.

A child is as much their mother's son as their father's son. At any point tracing the family back, you come to a fork in the tree and you can follow either branch. Great-Grandpa Baruch tries to follow the branches through the son, but hops aboard the daughter's line when that leads to the most credence for ďJewish royaltyĒ and larger greatness. Just for the record, the Cohen (High Priesthood) can only be passed through the male line. So Great-Grandpa Baruch is tracing his family through the daughter to connect to the more famous rabbi/scholar, but gives mention to the husband of the daughter to secure his entitlement to remain among the High Priests. It is shameful how women are dismissed as valued individuals in this heritage and are looked on as bargaining chips to claim a more glorious birthright. I don't think I would like Great-Grandpa Baruch. He devastated the lives of his daughters with arranged marriages.

I am a vestige of the Minz Dynasty, the tip on a twig that will grow no further, though other branches extend elsewhere. If my Great-Grandfatherís research is true, the dynasty sprouted from Rabbi Eliezer haLevi Minz the Ashkenazi, Minz referring to Mainz, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, where Rabbi Eliezer was born in 1388. The 29th October 1461 was one of several expulsions of Jews from Mainz in the fifteenth century. Eliezerís two sons escaped; Maharam taking refuge in Bamberg and my ancestor, Judah ben Eliezer haLevi Minz, arriving in Padua.

Should I feel proud of my heritage on my motherís side? I am derived from a family of great theologists and scholars who invested their intellects in the machinations of laws based on the ephemeral belief they needed to appease the arbitrary demands and vanity of a nonexistent god in which was posited all the wisdom of the Iron Age. Do I want to live in a world where unmerited pride is derived from the impressive but trivial ability to trace our family further back in time than our neighbors?

It vexes me. But then what do I do? I obsess about the hair on my ears. A nobler endeavor would be to reduce the struggle of existence and enrich the experience of life for humanity. So, I am at work on this genealogy to give to my mother on her birthday in February. Great-great-so-many-greats-grandfather, Rabbi Eliezer haLevi Minz was ninety-four when he died. My mother shows every promise of living longer.

Mr Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about the events and concerns of his life. If you've any comments or suggestions, he would be pleased to hear from you.

Selected Suburban Soliloquies, the best of Mr Bentzman's earlier series of Snakeskin essays, is available as a book or as an ebook, from Amazon and elsewhere.