|

(A sequel to essay 116)

To tell the story again... I sold my collection of fine press books to help finance starting life over again in Wales. In 2015, in fact, we sold or gave away nearly everything we owned in the USA to finance the cost. The objective was to take Ms Keogh back home to Great Britain, her homeland, and for me to immigrate.

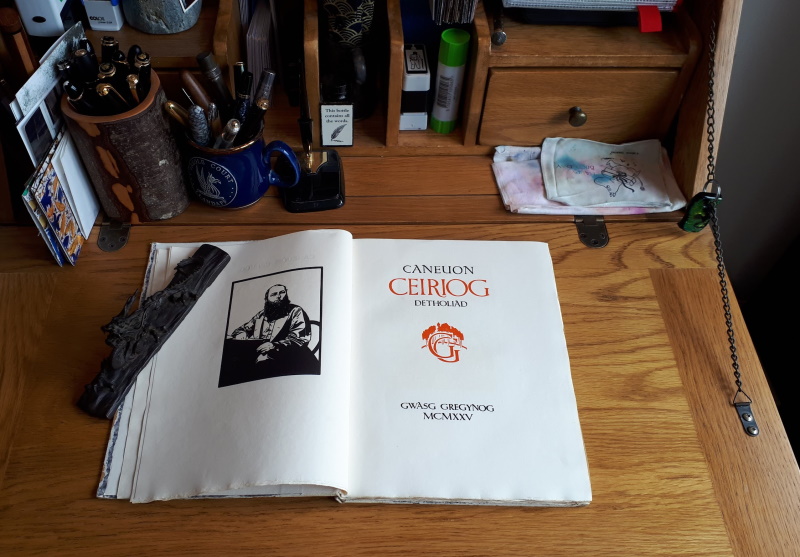

The love of fine press books has never left me, but I have not enough money nor years of life to rebuild a large collection. Still, there was one book on which I fell, spellbound. As I related in a previous essay, it appeared while browsing Jacobs Antique Centre, an old warehouse converted into an antiques bazaar. Three floors of stalls, and one of the stalls is devoted to books, the one belonging to Andrew, who you can occasionally see on the streets of Cardiff in a grey top hat and waistcoat, drumming up business traffic for the Antique Centre. The book was Caneuon Ceiriog.

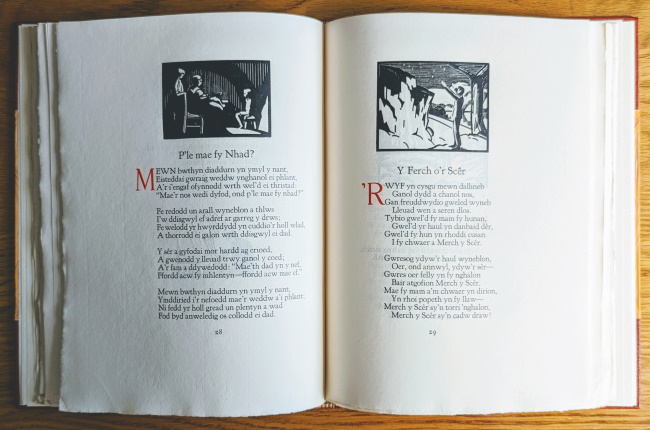

It is a gorgeous example of fine press work, illustrated with wood engravings by Robert Ashwin Maynard and Horace Walter Bray. Published in 1925, it was the third book issued by the Gregynog Press. On paper handmade by the Grosvenor, Chater & Co., it was perfectly imprinted with Goudy’s Kennerley Old Style type. The format appealed exactly to my taste in book design, except the binding was devastated. Also, the text was in Welsh. I neither read, nor write, nor speak Welsh. It took a couple of years before I surrendered and purchased the book.

I was determined to rescue the book. Its only issue was the binding being worn and tattered. It was quarter-bound with a heavy white linen on the spine and faced with grey marbled paper on the boards.

As I had written in an earlier essay, “I had decided this book was special, was significant to the history and culture of Wales. I was determined to finance this volume’s resurrection as a labor of love for the land that has adopted me, to repay its kindness.” I wanted a Welsh bookbinder.

I found one in Julian Thomas, listed in The Society of Bookbinders. His address was Ynyslas. Could it be more Welsh?

I sent Mr Thomas an email. “I am looking for a bookbinder, preferably Welsh, to replace the cover on a Gregynog Press book.” I also sent him a link to my earlier essay.

He wrote back, “Yes I would be able to rebind your Gregynog book and yes I am Welsh, born and bred in Cardiganshire, with a mother from Cwmbran.” He also added, “I served my apprenticeship under John Bowen who trained at the Gregynog Press back in the late 30’s.”

I did a Google image search on “Julian Thomas Bookbinder” and discovered his many beautiful creations. He was the perfect choice, if I could afford him. I sent him the book.

An email discussion commenced on what the new binding should be. “Half leather sounds fine to me,” Thomas wrote, “A full goatskin binding could not be confused with the original ‘specials’ which were bound in red Levant, a leather which is now unobtainable. They also had elaborately tooled boards. I have just checked in Dorothy Harrop’s book and see that a few were bound in blue Levant.” (I have since ordered a copy of Ms Harrop’s book, A History of the Gregynog Press.)

“But isn’t it beautiful?” I emailed.

Mr Thomas replied, “Yes very beautiful … It is nice to see it again and the condition of the inside is excellent.”

There is a long history of books being bound in Morocco leather, also known as Levant. It was considered the best and was typically goatskin. I wondered about using sheepskin, in keeping with everything Welsh.

Mr Thomas emailed back, “Your letter mentions Welsh sheep but I cannot help in that respect and would avoid using sheep as it is an inferior skin with not much strength. The only piece of Welsh bookbinding leather I know of anywhere is a small piece of orange goatskin I have here which was tanned in 1938 for Gregynog by the local tannery in Newtown. It was used as onlays on the cover of Shaw Gives Himself Away. I have photographed it with your book and the colour goes well with the capitals and GG press device. However, the off-cut I have does have blemishes and small scratches on it and also has lost some of its strength, so if I make a mistake thinning it, I will have no second chance. That put me to thinking that orange/terracotta would be a good colour to use as it complements the colour of the capitals and the GG. I attach a picture showing the grain of Harmatan terracotta goatskin which has a similar look to the old Levant grain and which I think would look better than the Newtown skin.”

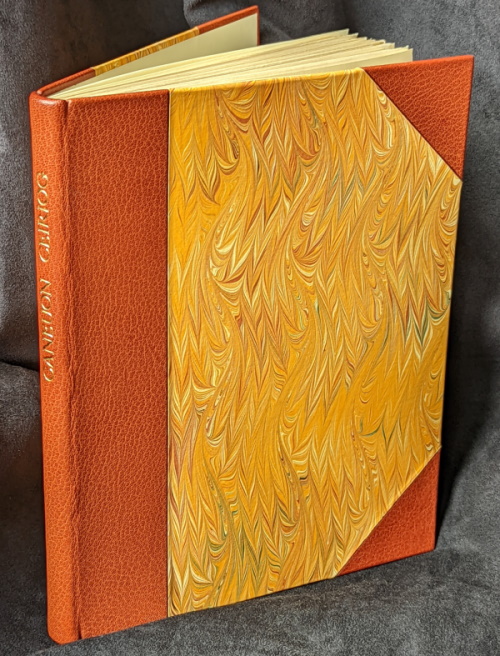

I went with the Harmatan terracotta goatskin.

While gilding makes the tops of books easier to wipe clean of dust, I find it garish. Mr Thomas had suggested it, but I told him I didn’t want it, unless he recommended it. He didn’t. We agreed to leave the deckled edges as is. He sent me a photograph displaying the three decorative paper sidings displayed alongside the Harmatan leather. I declined the traditional marbled paper by Victoria Hall, the Shepherds printed paper, and went with Italian marbled paper. He emailed, “The spine would be hand lettered with a typeface used on a number of Gregynog bindings. e.g. the special of Erewhon.”

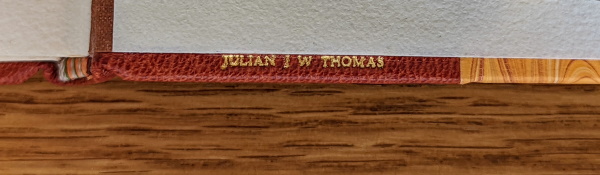

When it was all finished, he emailed, “I completed your binding this afternoon. Do you want me to stamp my name on the lower square of the back board just below the edge of the endpaper? See the attached picture of it in blind on a leather doublure but it can also be done in gold. The lettering is only 20mm long.”

Yes, absolutely, and in gold.

The binder's stamp.

And then came the email, “I am waiting for my finishing stove to warm up so I can tool my name on your Caneuon Ceiriog binding and I should be able to send it to you this afternoon, if I can find a suitable box.” He didn’t find a suitable box and so posting the book to me took an extra day. Because of his workload, Mr Thomas had warned me it could be four months before he could start on Caneuon Ceiriog. Now it was completed. Another day hardly mattered.

A warm afternoon, I spotted Andrew in top hat and waistcoat standing in The Hayes handing out brochures inviting pedestrians to visit Jacobs Antique Centre. I was overjoyed with the opportunity. I had him come up to the flat to see what had become of the Caneuon Ceiriog he sold me. He admired what had been done, but he asked if I thought I could recoup my investment. I said no, but that wasn’t the point of the endeavor. He appreciated and approved of my sentiment.

All that remains is for me to find a proper home for the book, since I can’t read it. Is there an appropriate library or museum to which I might donate it? Is there a hero of the Welsh language who would be honored with the gift of this book so beautifully bound? I am unable to part with it too quickly. I will try to learn to read Welsh.

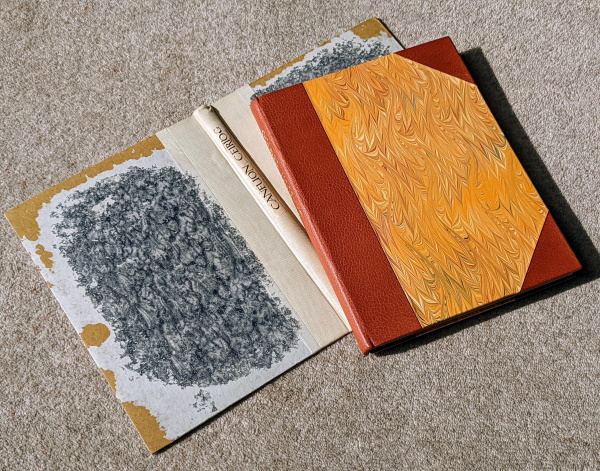

The new binding, with the old.

Addendum:

I could not have found a more perfect binder for this Caneuon Ceiriog. Julian Thomas’s work is in public collections in the UK and in private collections in UK, Europe, USA, Russia, Japan, and, for the time being, on my shelf in Cardiff. He was Conservator and Bookbinder at the National Library of Wales until he retired in December 2010, Head of Binding and Conservation and Manager of the Conservation Unit. He is also a member of the Society of Bookbinders, a Fellow of Designer Bookbinders, Instructor for the Society of Archivists Conservation Training Scheme, Accredited member of ICON [The Institute of Conservation], Honorary Life Membership of Archives and Records Association, and awarded the MBE for Services to Conservation Science and Bookbinding, and he’s Welsh.

![]()

Mr Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about

the events and concerns of his life. If you've any

comments or suggestions, he would be pleased to hear from you.

You can find his

several books at www.Bentzman.com.

Enshrined

Inside Me, his second collection of

essays, is now available to purchase.