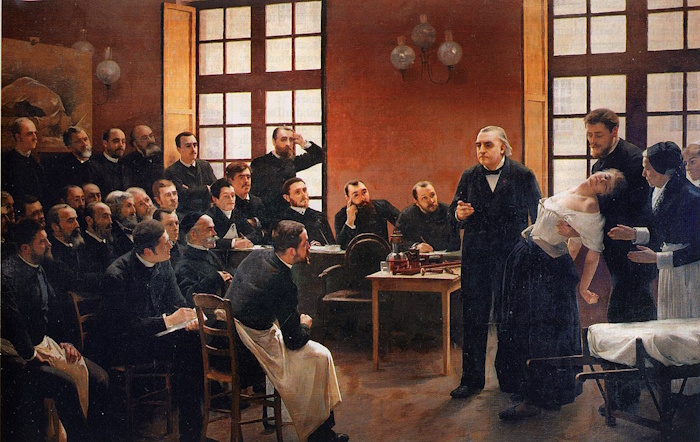

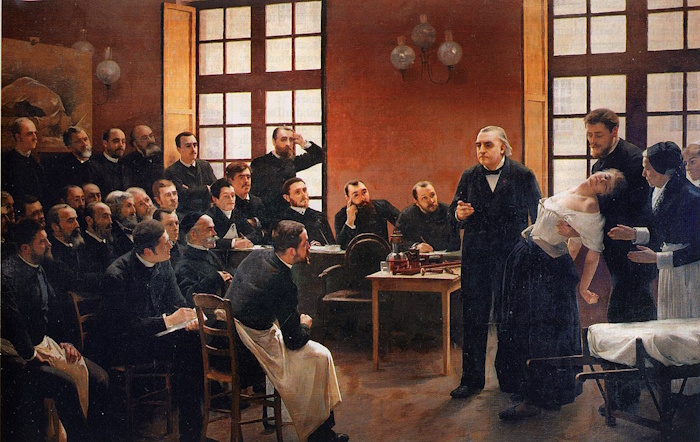

André Brouillet - A Clinical

Lesson at the Salpêtrière

Iconography of the Salpêtrière

Hospital

‘Father of neurology’, Charcot (1825-1893) identifies a new

disease: ‘hystero-epilepsy’.

I - Charcot Presents Hysteria

Immortalised by Brouillet in oils,

dark-garbed Charcot holds court

to the great, the good, the eminent

men of Paris, Vienna, seats of power,

exhibits an ‘hysteric’, white-clad,

swooning, her corset loosening,

shoulders rising erotic from the foamy

petticoat. The sober-suited men

are serious, observe, reflect,

mark the female as sensual

embodiment of her afflictions.

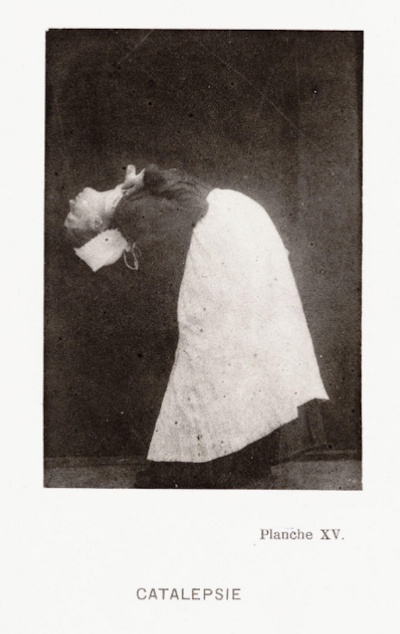

II - Playing to the Gallery

He shows me off, puts me under,

uses his huge tuning-fork.

Observe, gentlemen, the pronounced

impact of sustained sound on the patient.’

He puts me through my paces, runs me

through the stages of my illness.

I perform - as I must - the full range:

tear at my clothes and my flesh,

roll my eyes white, loll my tongue

one way, then another, bend my body

right back, act out the menace

of my ‘condition’…I look sideways

at the audience, some women

there, too, fine feathers, they! On the gad.

‘Observe, gentlemen, the unnatural

contortions of the spine, the facial convulsions.’

I breathe deep, sigh and sink, weak,

against the assistant, kind woman.

I play faint for them, hysterical,

plead with my arms, raise my skirts

high above my shift, beseech love,

grinding and swaying my hips.

(Easier than bearing Louis’s weight

and force and violence,

this acting out, this play.)

‘Observe, gentlemen, the successive phases, in sequence, of her

malady.’

My last act is the crucifixion,

hold my stiff arms and form a stiff cross,

hold it, hold it, hold it…. hold it

until he gives the sign.

The audience clap, respectful,

mouth to each other in wonder.

They must admire him, of course, but

how dare they pity me.

III - ‘Here comes the little man with

his mischief box!’

De Boulogne comes to take photographs,

charts scientifically the sufferings

of women held in the Salpêtrière,

explosive place of illness: dementia,

idiocy, erotomania, melancholic

catalepsy, paralysis, lethargy,

epilepsy. And megalomania.

The prisoners of Salpêtrière, their white arms

reaching through the bars of stone cells, call out

to him in mockery. Ribald, they deride

the size of his equipment, ask if he

is a real man. The laughter of these women

rings out freely, wild, coarse and crude, echoes

through the asylum corridors. An outlet.

Charcot relies on these photographs, ‘perfect

extension of the clinician’s eye’. He is poised

at the confluence of science, religion, art.

Does he ever doubt his truth, question truly

if his patients are ill - or fictionalised

victims of maladies observed, diagnosed

and birthed by him and his doctors?

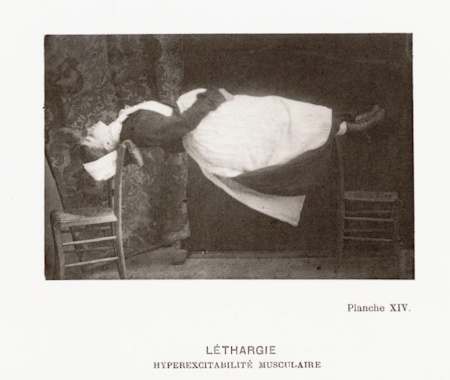

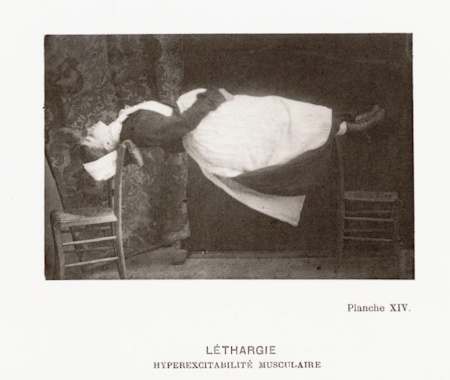

IV - Plate XIV - Observation

Twelve small photographs in sepia,

or maybe faded monochrome,

they evoke Victorian pornography,

images passed from grubby hand

to grubby hand, behind closed doors.

Assembled, four by three, they form

a stuttering narrative sequence,

as the slender white fish of the naked

body of a woman slips and flops

on a brass bedstead. Hands secured,

she arches her back in languor

or in ecstasy – or agony.

Does she evade or court the camera?

The doctors watch her slender frame,

ribs like bars, her shallow pelvic bowl,

triangle of dark hair at her groin,

her legs splayed as she writhes her body,

creates the ‘arc en cercle’ of the hysteric.

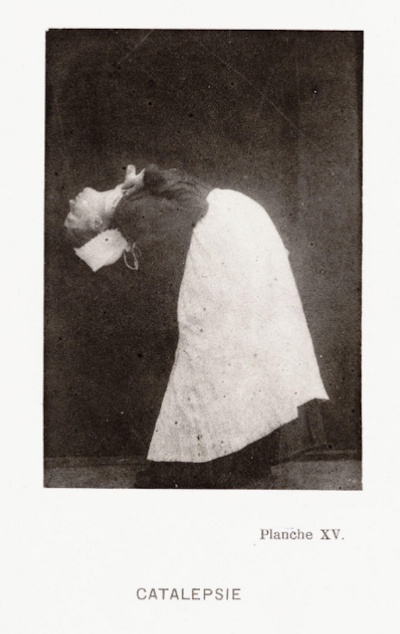

V - Plate XV – Case Study in Muscular

Hyper-Excitability

A woman floats - luminous white

against the darkness, head bent

back, eyes turned upwards, but closed.

This image evokes séances, witchcraft,

supernatural, female strangeness.

In truth, her tensed body is so stiff,

she is a board between two chairs.

Her demure hands are clasped tight

on her belly, over her ovaries,

pressing them down, making them

submissive, as she is, for the camera.

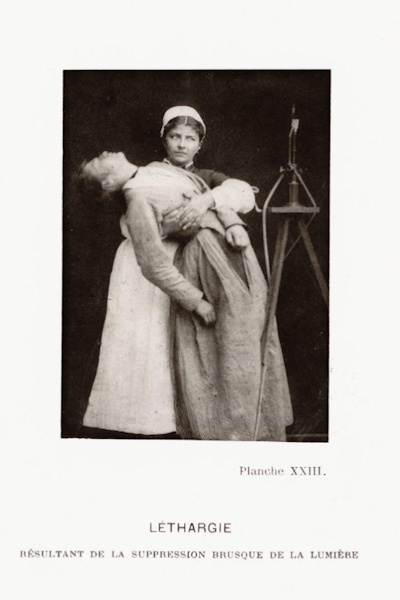

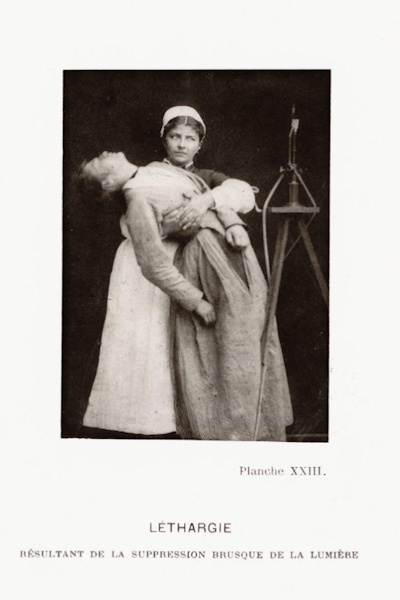

VI - Plate XXIII – ‘a gifted hysteric’

Augustine gives him exactly

what he wants. Allows him

to pose her, fix her image

in the hysteric’s different states:

eroticism, menace, lethargy.

A haunch of meat, a slab of flesh

in some medieval shambles, she

is as naked as grave Charcot

is overdressed. Or wears a white shift

that drifts from her shoulders, rides up

her legs, reveals decolletage

and rounded thighs, her arms outstretched

in gentle beatific attitude.

They work, doctor and patient

in fecund collaboration,

to fetishise the female body,

identify the pandemonium

of women’s infirmities.

VII

Legacy

‘Napoleon of the Salpêtrière’,

Charcot makes his name, leaves his gifts

to science, to male posterity.

Her charms failed, utility

diminished, Augustine smashes

windows, screams, shreds

the strait-jacket they make her wear.

Escapes - disguised in male attire.

Amanda Brookfield

If you have any thoughts about this poem, Amanda Brookfield

would be pleased to hear them